As a VC, lawyer, and entrepreneur, I’ve seen the good, the bad, and the ugly of issuing SAFEs. The Simple Agreement for Future Equity, or SAFE, as we lovingly call it, is a great tool to help early-stage entrepreneurs raise money. Compared to a priced equity round, SAFEs are often easier to negotiate, quicker to execute, and result in much lower legal fees.

But they can also be silent killers. For all of their virtues as a fundraising tool, I have seen young companies get passed over for a current investment due to mistakes in past SAFE fundraising. This article shines a light on how SAFEs can be dangerous, the mistakes to avoid, and how entrepreneurs can use them effectively.

While the SAFE is a very popular instrument for early-stage financing, this article also applies to convertible notes, which are another common fundraising tool. I’ll assume in this article that you know how a SAFE works. If you want a refresher, Cooley has a good primer here. Y Combinator, which created the SAFE, publishes model documents here.

Danger #1: More dilution than you think

The biggest problem that SAFEs can create is ownership dilution for founders. At the early stages of fundraising, founders might not consider how much dilution they are taking on by issuing SAFEs to their investors, since SAFE dilution doesn’t show up on the cap table. This can have disastrous effects once the SAFEs convert to equity in a future priced round of financing, when the math just doesn’t work out for investors.

The best way to combat dilution shock is to track SAFE dilution before SAFEs convert to equity.

Here’s a simple example: Elizabeth, founder of FinnTech, a Finnish technology company, raises her first $1 million in pre-seed financing on SAFEs with a $5 million post-money valuation cap. She owns 85 percent of the company, having set aside 15 percent for employee stock grants.

FinnTech is doing well and attracts the eyes of angel investors. Elizabeth happily acquiesces to their interest and raises an additional $1 million on a $7 million post-money valuation cap. The terms are more in her favour and Elizabeth still owns 85 percent of the company, right?

FinnTech is ready to ramp up sales and it’s time to raise a bigger round of financing. Elizabeth signs a term sheet with TheBestVC for $5 million on a $20 million post-money valuation. Fantastic! Elizabeth does some mental math — a $5 million raise divided by a $20 million valuation means she is selling 25 percent of the company. Not bad for dilution.

In reality, Elizabeth will take on more than 50 percent dilution, with her ownership dropping from 85 percent to 42 percent. The SAFE investors will hold 26 percent of the company, TheBestVC another 25 percent, and the stock option pool will sit at just 7 percent. Elizabeth went from a supermajority holder to having lost control of her company.

This result can be shocking to both founders and investors. Unfortunately, it is common. Investors may find it difficult to invest in a company with too many outstanding SAFEs because it becomes difficult to achieve their target ownership while keeping founder and employee ownership high enough.

The best way to combat dilution shock is to track SAFE dilution before SAFEs convert to equity. Create a dynamic cap table that lets you model your ownership in different fundraising scenarios. This will help you be more strategic about the money you raise and think carefully about the terms you are accepting. If you need help with this, ask your investors, or your lawyer.

Danger #2: Valuation cap is not valuation

One of the key terms of a SAFE is its valuation cap — the highest valuation that SAFE investors could effectively pay for your company’s equity. This is a handy metric for a quick dilution calculation. For example, if you sell $1 million of SAFEs with a $10 million post-money valuation, then you have sold at least 10 percent of your company.

Sometimes entrepreneurs or investors look at the valuation cap in a SAFE as the actual valuation of their company.

Sometimes entrepreneurs or investors look at the valuation cap in a SAFE as the actual valuation of their company. This is problematic when it comes time to raise a priced financing round and any price below the valuation cap becomes a ‘down round’ that must be avoided. This can lead SAFE investors to push back against the financing, or cause entrepreneurs to hesitate and push for a higher valuation.

High valuations are nice, but they can cause problems for early-stage startups when raising follow-on financing. For many companies, the early stages of growth are about developing your first product and understanding the needs of your customers. Settling on a valuation at these stages can over- or under-value your efforts, leading to heartburn at the next financing.

One of the great features of a SAFE is that it does not require the company to be given a valuation. Eschewing a formal valuation at the very early stage has benefits for the company and the investor alike. Take this advantage. Your valuation cap is not your valuation, it’s just dilution protection for your investors who are taking an early bet on your company.

A quick aside: SAFEs can use a post-money or a pre-money valuation cap. A post-money SAFE makes it easier to track dilution, but is generally more favourable to investors. Back in 2018, Y Combinator changed its model SAFE from a pre-money to a post-money valuation cap, and much of the industry has followed. Make sure you understand which type of valuation cap your SAFE uses because it can have a real impact on your next equity financing.

Danger #3: Nonstandard terms

One of the best parts of a SAFE is that the documentation is short. Clocking in at just seven pages, the industry-accepted Y Combinator SAFE is easy to understand when compared to the hundreds of pages of legalese involved in an equity financing. Take an hour out of your next weekend to read the Y Combinator model SAFE — trust me you’ll be surprised at how much you will learn.

Even though the SAFE appears simple and…safe, it can also be easily edited to include onerous terms that will make future investment difficult. I have seen SAFEs edited to give investors outrageously one-sided advantages, such as guaranteed board seats, off-market veto rights, and broad control over the company. Sometimes these are warranted, but often they are not.

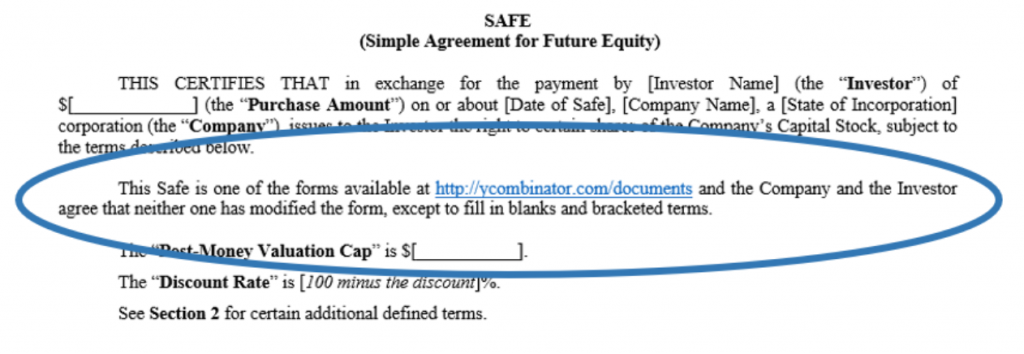

Terms like these will make it more difficult for future investors to fund your company because you have effectively sold more control of your company than is expected. Fortunately, you have two very useful tools at your disposal to avoid this trap. First, look for this sentence in any SAFE you receive:

This is a good-faith statement that the SAFE has not been edited to change any of the terms other than those that are most commonly negotiated.

This is a helpful start, but many fair SAFEs make other reasonable edits and so cannot include this statement. Enter the second tool you have at your disposal: the ability to create a blackline against the Y Combinator model SAFE. You can do this with Word and Google Docs, or you can ask your lawyer to do it for you. A blackline will highlight every little change that has been made to the SAFE so that you (and your lawyer) can make an informed decision on exactly what you are signing.

Solutions in a SAFE world

By no means should you as an early-stage entrepreneur stop using SAFEs to fundraise. Their simplicity and speed make them fantastic fundraising templates. Just be careful — by tracking exactly how much dilution you are taking on and carefully understanding the terms of the agreement, you will set yourself up for success in future rounds of financing. If anything seems unclear, your investors, mentors, and lawyer will certainly be happy to help.

Feature image courtesy Unsplash.