It doesn’t take a lot of study and analysis to recognize that you can get a lot more done in a day using a smartphone and a laptop than a fax machine and an abacus, or a pencil and legal a pad. But the benefits of these leaps in personal productivity have not been matched with increases in pay or time off from work.

Sir Christopher Pissarides, London School of Economics

“If it’s left completely unregulated, AI is going to give rise to even bigger inequalities than previous technologies.”

According to the Economic Policy Institute, during the early internet age between 1973 and 2013, productivity increased by 74 percent while average hourly compensation increased by just nine percent, once adjusted for inflation. Workers were indeed getting more productive thanks to significant advancements in technology, yet they rarely benefited from those gains. In fact, workers in the age of smartphones, cloud computing, and broadband internet are still working the same hours as those who were around during the invention of the lightbulb—and are getting paid about the same as those who were around before the invention of the personal computer.

“Why would it be different for AI?” asks Nobel Prize–winning economist Christopher Pissarides. Sir Christopher—who was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II in 2013 and has asked that we not call him by his formal name, but we couldn’t resist—made global headlines in April 2023, and again that December, for announcing, then reaffirming, his belief that AI will usher in a four-day work week in the coming years.

Speaking to us from his home in England, the London School of Economics professor explains that he made his headline-grabbing declaration after the public release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT. That, he says, gave the world a glimpse into just how far AI had come in recent years and a sense of what the future may hold.

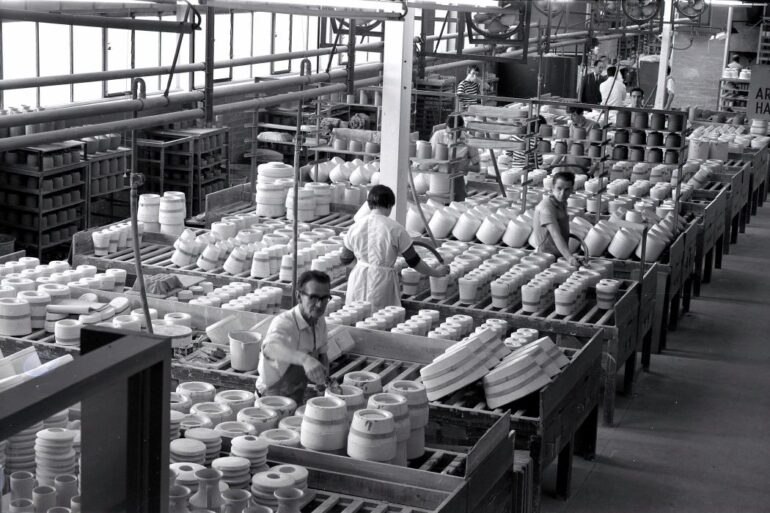

“If it’s left completely unregulated, AI is going to give rise to even bigger inequalities than previous technologies,” he says. Sir Christopher explains that previous waves of technology only furthered the gap between the haves and the have-nots, hollowing out the middle class. As more workers feel left behind by these advancements, they’re losing faith in once-trusted institutions. The result is our current state of heightened social division. Advancements in robotics, for example, made manufacturing cheaper and manufacturing companies more profitable while eliminating countless middle-class, low-skill jobs. “Now AI is having the same impact, so we need to regulate it if everyone is going to benefit,” he says. “If you’re not going to pay workers more, and yet they’re contributing so much more to your productivity [thanks to AI], then you might as well give them some more time off.”

Sir Christopher—like Bill Gates—believes the proliferation of AI will be different from the productivity-boosting technologies that came before. Unlike previous waves of innovation, new AI tools are becoming widely available at reasonable price points and with relatively minimal barriers to entry. For example, you don’t need to know how to code or hire a team of engineers to enjoy the productivity benefits of AI technologies. Despite the minimal costs to individuals, the potential upside is massive, especially for knowledge workers. “AI enables us to organize work in different ways, including remote working, including postponing things—doing them in our own time, because everything will be recorded—and it’s through that there will be productivity gains,” Sir Christopher says. “So if you’re going to be able to organize your work in a flexible way…then it makes it a lot easier to pack everything into four days and not lose any income, because you will become more productive with the new technology.” Proof of that exact dynamic came minutes after our meeting, when Sir Christopher was provided an AI-produced summary of the call, along with a transcript and video, all of which were auto-generated by a service that costs $8 per month.

Just as the industrial revolution changed the kinds of skills we needed to thrive in that economy—specifically, from our most human traits to our most robotic ones—AI is poised to have an equally dramatic (albeit opposite) effect.

In a world where affordable, broadly available technology can assist with countless workplace tasks, the individuals and organizations that succeed will be those that work smarter, not harder. However, when we talk about AI, we should acknowledge that most people still associate the technology with widespread job displacement.

If the doomers and gloomers are right, AI will usher in a world where most will be happy to get any work they can. But we think those predictions are unlikely to come to fruition. Instead of workforce displacement, most experts believe AI will usher in a workforce pivot, rendering some jobs obsolete while giving rise to roles and industries we can’t yet imagine. Remember, people in the early nineteenth century panicked when new technologies started to displace workers in the world’s largest industry, agriculture, because they couldn’t have possibly imagined the jobs that would be created in the future. After all, it would be pretty hard to explain to a farmer in those days that their children would have plenty of job opportunities in the automotive sector, before the invention of the automobile. As with that period of rapid economic change, it’s similarly impossible for us to know what kinds of jobs AI will create. But, rest assured, there will be room for human labour.

RELATED: The future is a four-day workweek

However, just as the industrial revolution changed the kinds of skills we needed to thrive in that economy—specifically, from our most human traits to our most robotic ones—AI is poised to have an equally dramatic (albeit opposite) effect. When powerful machines can do repetitive work that prescribes to a formula, there will be a greater need for humanity to demonstrate its ability to think outside the box, to hone our creativity, problem-solving, critical thinking, and other inherently human traits.

Once upon a time, accountants spent most of their time doing mathematical equations in a back room by hand. Organizations needed teams of bean counters to do basic arithmetic and to check each other’s work, but the role was considered more in the realm of grunt work than the stuff of corporate leadership. Though they worked with pen and paper, the accounting profession was intentionally designed to mimic the assembly lines of industrial-era factories. Until the 1960s, electric calculators cost more than a team of human accountants and required about as much physical office space. The first electronic desktop calculator, ANITA (which stands for A New Inspiration To Arithmetic/Accounting), hit the market in 1961 and sold for about $1,000 (or about $10,500 in today’s dollars). By the end of the decade, technology manufacturers like Sharp, Canon, Sanyo, and Texas Instruments introduced a range of portable calculators, which came in closer to $2,000 in today’s money. By the mid-1970s, numerous competitors in the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and Japan entered the market, offering calculators designed for professionals as well as some priced low enough for everyday users. Today, you can buy a calculator that fits on a watch for $30. So why do we still have accountants?

Image courtesy Unsplash. Photo by FIN.

If the primary function of the accounting profession was to crunch numbers, then a machine that could do that task with a higher degree of accuracy in a fraction of the time should have wiped that industry out entirely. Instead, as the affordability and availability of calculators skyrocketed, so did the number of accountants in the United States. In 1960, before the proliferation of the calculator, the “Big Eight” American accounting firms employed 1,071 accountants; by 1981, they collectively employed more than 7,000. Today, there are more than 1.56 million accounting and auditing professionals in the United States, with an estimated annual employment growth of six percent.

Today the accounting profession has been elevated from backroom bean counters to chief financial officers, often one step removed from the highest position in the organization. In fact, these days it’s quite common for CEOs themselves to rise out of the accounting discipline. A 2019 study of the Fortune 100 found that 22 percent of the world’s top CEOs began their careers in finance, the second-most-popular pathway after operations. Rather than rendering accounting positions obsolete, the widespread availability of calculators has allowed accountants to ditch the low-level number crunching and add entirely new kinds of value to the organization.

Their rise from the backroom to the executive suite also had a significant impact on the skills required to be an effective accounting professional. Today, you can’t make it to the highest levels of the profession simply for being good at math. Accountants are instead required to use the tools at their disposal—including the calculator, spreadsheets, AI, and countless other more complex types of software—to act in more of a high-level advisory and leadership role.

In a world where affordable, broadly available technology can assist with countless workplace tasks, the individuals and organizations that succeed will be those that work smarter, not harder.

Technology that was once predicted to eliminate the role has instead transformed the kinds of skills necessary to succeed, from the more robotic traits to more human skills—like critical thinking—while elevating the value of the position itself. If this transformation happened to accountants, why can’t it also happen to other technical roles that are poised to be disrupted by the upcoming wave of AI innovation?

Yes, AI’s impact will be technological, and in terms of pure output, it will increase our capacity to do more in less time, but that’s just the beginning. AI is also poised to usher in dramatic changes to the economy, the labor market, the social contract between employers and employees, and the role work plays in our lives. Until recently, the dramatic leaps in innovation have had little impact on the average person’s wealth or quality of life. As we enter the age of AI, we have a unique opportunity to change the narrative, to use the gains promised by technology to improve living standards, and to help restore our faith in our institutions and each other.

Adapted by permission of Harvard Business Review Press. Excerpted from Do More in Four: Why It’s Time for a Shorter Workweek by Joe O’Connor and Jared Lindzon. Copyright 2026 Joe O’Connor and Jared Lindzon. All rights reserved.

Feature image courtesy Unsplash. Photo by East Riding Archives.