The next big thing in connectivity is elusively, almost comically, small. As cities get denser, and its citizens’ wireless needs more explicit, carriers are looking to new technologies as ways to fill in the coverage gaps left by mounting large antennas on increasingly crowded rooftops, or towers whose signals can’t quite reach every device it promises.

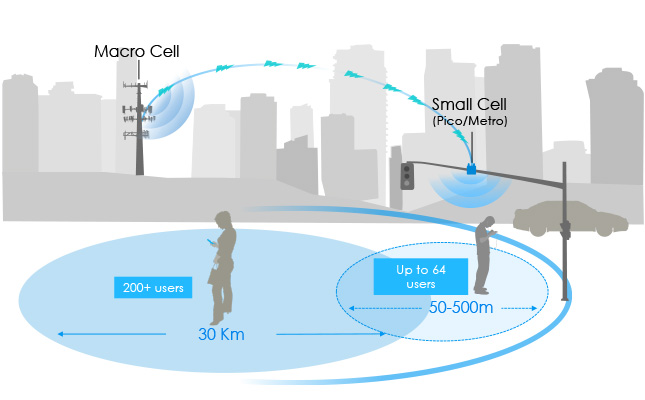

Dubbed “small cells”, these diminutive boxes are often installed on the street level — on light fixtures, or utility polls — or even in peoples’ homes, as ways of boosting cellular signals indoors or in dense urban areas. With a range of between a few metres to up to several kilometres, the category itself is a vibrant ecosystem of suppliers and distributors working with carriers to improve their coverage as demand for wireless data burdens existing “macro” cell infrastructure.

Most Canadians don’t care how they connect to their carrier’s wireless network, as long as the signal is strong and the performance vibrant. In large cities such as Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal, density, both in terms of people and the signal-reflecting nature of tall buildings, has forced carriers to pursue a small cell strategy that, in 2016, will likely double in deployment from a year ago, according to a tower executive familiar with Canadian carriers’ plans.

Earlier in the month, SaskTel announced that it deployed Huawei’s Lampsite technology, a variation on existing small cell products, in two buildings at the University of Regina. Scott Bradley, Huawei Canada’s VP of corporate and government affairs, said the university had been looking to shore up its wireless coverage inside the thick concrete monoliths that comprise much of the campus.

Under the supervision of SaskTel engineers, the university’s Faculty of Engineering and Applied Sciences oversaw the first Canadian deployment of Lampsite, a variation of small cell technology that creates a Heterogeneous Network, or HetNet, within its service area.

Now in its second generation, Lampsite generates three signals — WiFi, 3G (HSPA+) and LTE — and “offers” devices the best one seamlessly depending on a number of factors. When deployed inside a building, a single box can connect to a carrier’s network through a provisioned ethernet cable, or by picking up a weak signal from a remote tower and amplifying it.

“Lampsite is part of the evolution towards 5G,” said Bradley, whose company is pushing to be the primary hardware provider to Canadian carriers for the next-generation wireless standard. The idea is that under 5G, devices such as smartphones, tablets, wearables and other connected products will be able to simultaneously send and receive data from a number of sources; effectively, the distinction between WiFi and cellular will be eliminated.

In the meantime, small cell deployments will be increasingly common in densely-populated cities as data needs proliferate. In the U.S. and Canada, locations such as sports stadiums and school arenas are already well set up for small cell offloading. According to Cisco’s Visual Networking Index report, released last February, by the end of 2016 over half of all worldwide mobile traffic will be offloaded to a WiFi network or cellular equivalent, known as a femtocell.

In 2015, Telus reportedly deployed around 2,000 small cells in Vancouver and Calgary, a number that eclipses that of Rogers and Bell. While no carrier has shared official numbers of small cell deployments, Telus has reportedly been able to reduce deployment costs because it co-owns with BC Hydro a number of utility poles that are classified for cellular equipment use. Bell and Rogers deployed around 400 and 50 respectively, but every major Canadian carrier has yet to see costs of small cell equipment drop low enough compared to their relative coverage area to match the economies of scale of so-called macro towers, which cover much of Canada with 3G and 4G LTE signal.

One Canadian company, however, may single-handedly make small cells mainstream across the country — or at least in the western half of the country. Shaw Communications, which in 2011 reversed course on its decision to deploy a cellular network after spending $189.5 million in 2008’s AWS spectrum auction, currently operates some 75,000 WiFi hotspots across Western Canada and parts of Saskatchewan, Manitoba and western Ontario. While Shaw has yet to comment on its plans for Wind Mobile, which it is purchasing for $1.6 billion, one obvious measure to shore up signal is to augment its existing WiFi infrastructure with a network of small cells broadcasting what will inevitably be high-speed LTE through those existing nodes. Shaw expects to spend $250 million throughout this year and into 2017 to improve Wind’s network, eventually rolling out a robust LTE network once handsets are available that support the just-ratified AWS-3 standard.

Ultimately, small cells are useful to prevent waste in deployments of high-frequency spectrum on which many Canadian carriers have spent millions of dollars accruing. Whereas 700Mhz spectrum already exists to penetrate thick walls and travel longer distances, high-frequency spectrum like AWS and 2500Mhz can carry more data at higher speeds. Coupled with small cells, carriers can more easily fill in dead zones that, in large cities awash in glinting spires of modern capitalism, pose challenges for the engineers tasked with ensuring fast, ubiquitous connectivity.

This article was originally published on MobileSyrup.