With all the recent movement within Canadian digital health, in funding, partnerships, and even governance, the stage could be set for big growth and changes. But with new changes, come new barriers and challenges for companies looking to commercialize.

One question that has lingered in Canada’s complex healthcare system may be one of the industry’s biggest hurdles to adopting these innovations. That question: who’s the buyer?

“You can’t do healthcare innovation unless you figure out who pays.”

“You can’t do healthcare innovation unless you figure out who pays,” said Balaji Gopalan, co-founder and CEO of MedStack, which has developed a Toronto-based compliance solution used by many healthcare apps. “It’s a really complicated question.”

“We do need to demystify procurement. That becomes a big barrier to tackling healthtech innovation,” said Tara McCarville, national health industries leader at PwC Canada. “You can have this great tech, this great solution, that is addressing a major problem in healthcare, but it’s not clear who’s writing a cheque to address that problem.”

McCarville told BetaKit that 70 percent of health spending in Canada is from the public sector. Unless a public payer has the ability to spend money on a healthtech solution, it can become incredibly difficult for Canada’s healthcare system to adopt new technologies.

RELATED: Medstack raises $2.4 million oversubscribed seed round led by Telus Ventures

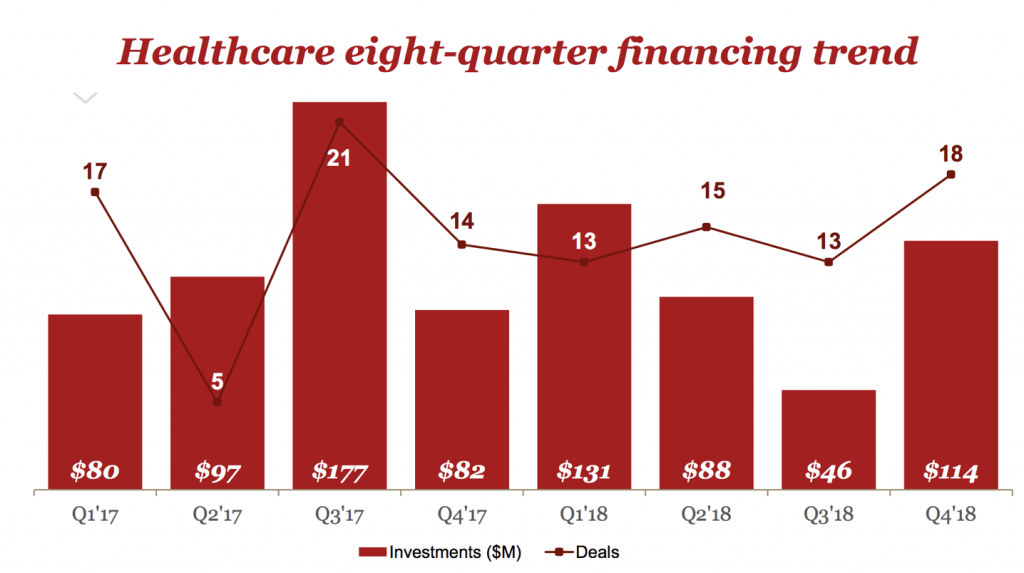

PwC Canada’s most recent MoneyTree report found that healthcare investments in Canada in 2018 totalled $378 million USD, a 13 percent decline from the previous year. On the other hand, PwC also found that funding for Canadian digital health companies rose to $177 million USD, up 35 percent compared to 2017.

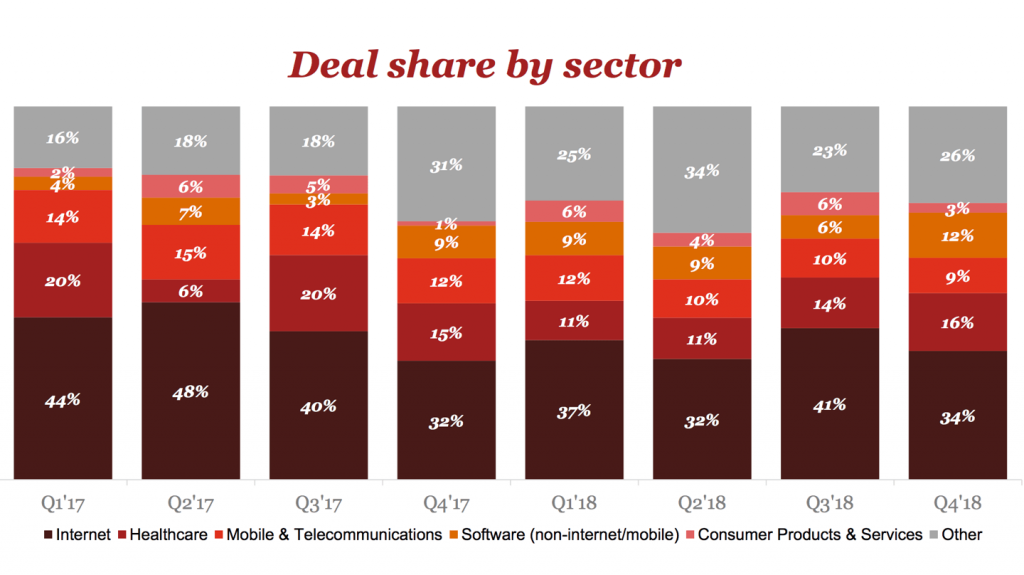

Despite a 13 percent decrease in healthtech investment, the sector still remains one of the largest in terms of interest. PwC found, on average, healthcare is the second largest sector in terms of deal share, eating up anywhere from six to 20 percent across all sectors in the country. For Q4 of 2018, PwC found it took up about 16 percent of the deal share across all sectors. But, despite the size and scope of Canada’s healthcare industry, adopting these new innovations has proven challenging.

Procurement a ‘major hurdle’

In a 2016 survey across Council of Academic Hospitals of Ontario (CAHO) members (Ontario’s 23 academic research hospitals), 76 percent of respondents reported policies, directives, and procurement regulations as “major hurdles” to adopting innovation within their companies.

CAHO also released a guide on Ontario’s Broader Public Sector Procurement Directive, which is based on five principles for organizations following the procurement process: accountability, transparency, value for money, quality service delivery, and process standardization. Models such as negotiated requests for proposals (RFPs), competitive dialogues, partnerships, reverse auctions, and best and final offers, are all accepted procurement strategies under the directive.

“You have tech companies who can’t possibly enter into those types of procurements because of the complexity.”

But that directive is specific to Ontario. The problem, McCarville said, is that Canadian healthcare overall has a complicated procurement system, with 14 government jurisdictions (the federal government, 10 provinces, and three territories), each with its own legislative framework, and tightly-managed budget. She said this creates a very complex healthtech ecosystem, for both consumers and the companies operating within it.

“Different provincial governments have different policies around what they’ll pay for,” she said. “So you have these amazing solutions, but the business case is not clear.”

If a company in British Columbia, for example, is developing a healthtech solution that it wants to sell across all jurisdictions in Canada, the company will have to contend with public sector guidelines (which differ by province, but tend to be fairly similar), as well as the various laws and regulations in place to ensure taxpayer money in each jurisdiction is being spent responsibly.

“The procurement standards are, quite rightly, extremely rigorous,” McCarville said. She noted, however, that “now, you have tech companies who can’t possibly enter into those types of procurements because of the complexity associated with them.”

The Information Technology Association of Canada (ITAC) released a 2018 whitepaper detailing recommendations for how Canada can accelerate the adoption of digital health technologies. It stated that Canada’s public and private sectors should be far more involved in fostering sustainable investment, standardized procurement practices, and scaling innovation across the Canadian digital health marketplace.

“Procurement practices within digital health have become increasingly centralized, resulting in a smaller number of opportunities that are correspondingly much larger,” ITAC wrote. “In spite of these forces, procurement practices are often different in each jurisdiction, and even within jurisdictions. The rules of engagement are also becoming much tougher and Canadian jurisdictions are simply not keeping up to their contractual obligations.”

The problem isn’t private equity

While PwC reported that healthcare investments were down 13 percent year over year, it also saw an increase in investments from Q3 2018 to Q4. Canadian VC-backed healthcare companies raised $114 million USD, according to PwC’s MoneyTree report, suggesting that private investors are excited about innovative healthcare solutions.

McCarville argued that there needs to be interest from players outside of private equity.

“You need a business case,” McCarville said. “Someone has to write a cheque for [a solution]. And I don’t mean private equity, I don’t mean seed funding…it’s the commercialization of those companies, where some of its major barriers have [existed], not just in the Canadian marketplace, but beyond.”

RELATED: Telemedicine platform, OnCall Health, raises $2 million CAD

According to Public Services and Procurement Canada, the department responsible for the procurement for other government departments, the federal government is one of the largest public buyers of goods and services in Canada, purchasing approximately $16 billion every year on behalf of federal departments and agencies. McCarville said although the various levels of government play very important roles in ushering in new, workable strategies for procurement, and this problem does not fall on the shoulders of one stakeholder alone.

“I think there are a number of different players in the ecosystem that need to continue to push the envelope here,” she said. “I think it’s up to organizations like [PwC] to say ‘Some amazing innovation is underway, and we need to think differently in order to feed the health tech sector in Canada and beyond.’”

Access to data also a challenge

Procurement is not the only barrier to healthtech innovation adoption in Canada. With the development and rapid pace of new technologies able to collect vast amounts of health information, access to data in healthcare has surfaced as an emerging and significant topic. Access to healthcare data, which companies like Dot Health are aiming to tackle, by offering users access to their personal health records through its app, has also become another serious challenge in Canada’s health industry.

“The issue with access to data becomes that data ends up sitting in the different systems where it gets collected, whether that’s in a pharmacy, the primary care physician’s office, or with a personal trainer,” McCarville said. “If you had your mortgage at one bank, your chequing account in another, and a credit line at a third place, you can manage it, but it would be a lot easier if it were all in one place. It’s not a lack of desire of Canadian consumers to have access to that. But how do you provide access?”

Dot Health, which was founded by Huda Idrees, aims to enable consumers to access their own data. Idrees said because healthcare data lives in the ether, and can’t synchronize, she wanted to build a service enabling real-time access that can be controlled by the client.

The company recently partnered with Maple, a platform for on-demand access to healthcare providers, to launch a virtual care platform allowing users to share full medical history with Maple’s network of online healthcare providers. Dot relies on these partnerships to gain access to real-time feeds of information, without having to deal with each system of care individually.

“Health data is our currency,” Idrees told BetaKit. “We need to be able to deliver updated, continuous, longitudinal health data to customers in order to retain them and make ourselves valuable to them.”

McCarville noted that there are a number of AI and blockchain-powered solutions doing work to consolidate access to health data, and many of those solutions are made possible through partnerships.

In 2018, digital health deals increased from 17 in 2017 to 30 in 2018, according to the MoneyTree report. Even in the first few months of 2019, Canada has seen a groundswell of activity in the digital health space. Beyond Maple and Dot Health’s partnership, VirtualMED, for example, recently joined forces with US-based HealthTap to offer an AI-powered virtual care service. In March, Dapasoft, a healthtech iPaaS (integration-platform-as-a-service) company announced that it merged with iSecurity, a privacy and security consulting company.

In light of all these new partnerships and product launches in virtual care, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA), the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, and the College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC) are launching a task force to examine virtual care technology and how it can improve access and quality of care for patients across the country.

“It is time for our policies and regulations to evolve to today’s available technology,” said Gigi Osler, president of the CMA. “Removing barriers can lead to improved access to care for all Canadians.”

“I think the regulation is reacting to the creation of these alternative methodologies and care,” said Gopalan. “[These companies] have forced us to have a conversation about a multitude health care system. I think that forced the predominant healthcare system to sit up and take notice.”

Despite the barriers to procurement, accessing data, and lack of clear regulations in Canada’s complex ecosystem, McCarville said she sees a great deal of promise for Canadian healthtech. As the sector improves, she expects to see people and organizations helping demystify how new technologies can work together to address some of these challenges.

“I think there’s a lot of amazing, thoughtful entrepreneurship underway, leveraging Canadian-centred tech and even global tech to address some of the big challenges in health care,” she said. “Canada is such an important healthtech hub, and I’m very bullish that’s going to continue to happen.”

BetaKit is a MoneyTree media partner.