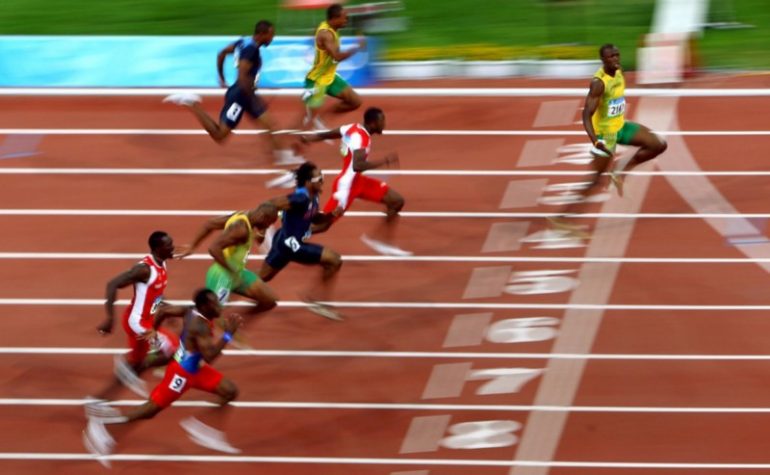

If you’re not first…you’re last. It’s the rare saying echoed by both Ricky Bobby and startup founders everywhere. But, while this adage might have some truth in sports, it can be dangerously misleading for entrepreneurs.

In business circles, this idea of being first to market is referred to as first-mover advantage. The thinking is that if you can get a new concept out before anyone else, you’ll be able to build a brand and a following while everyone else is asleep at the wheel. By the time competitors enter the picture, you’ll have a huge head start and enjoy market leader status for years to come.

As a second-mover, you benefit by having a clear, real target in your sights.

There’s something intuitive and attractive about this theory. And it’s not hard to find examples. Hoover came out with the first mass-produced vacuum in 1908 and dominated the market for decades. In the late ’70s, Sony unveiled the Walkman — the first “personal stereo” — and ruled the roost all the way until, well, the iPod.

More recently, Amazon created the first online bookstore and has never looked back. Today, companies are racing to bring the first truly autonomous vehicles, the first business-ready VR, and the first full-fledged AI assistants to market.

But, if a growing body of contemporary examples count for anything, I’d argue that the first-mover advantage is actually becoming more of a first-mover liability. Especially in an environment where technology is changing fast and markets are still evolving, being first to market is hardly a guarantee of future success.

Microsoft came up with a tablet computer a full decade before the iPad was unveiled, but the market just wasn’t ready. Friendster beat Facebook to the punch, but was beset by huge server and infrastructure costs, among other challenges. In recent years, Snapchat has pioneered everything from disappearing images to face-morphing lenses…only to see Facebook co-opt nearly every key feature.

Ultimately, of course, it’s not who’s first to market but who’s best to market. In fact, in my entrepreneurial experience, second (and third and fourth) movers actually enjoy some serious advantages:

You’ve already got market proof

Being first to market usually comes down to a stroke of luck. It’s the ability to win over customers and keep them coming back over the long haul that’s the real differentiator.

Hootsuite wasn’t the first social media management tool out there. When we launched our platform in 2009, a host of companies already had competing offerings. And that represented a huge strategic advantage … for us. For starters, we knew that demand existed — there was market proof in the form of thousands of users. Plus, these competitors had already done the heavy lifting of defining a brand new product category. They put “social media management” on the radar at large companies, so when we made our first sales calls, buyers knew what we were selling.

You have the luxury of cherry-picking

First-movers are often driven more by technology than by customer need. They race forward to get an innovation to market, without fully understanding who will use it, how to charge for it, or even what features are actually helpful. Our early competitors invested heavily in developing new features, some of which were helpful, many of which weren’t. As a second-mover, we had the luxury of cherry-picking the best of the bunch — scheduling, approvals, analytics — and incorporating them into a single platform. And we could also learn from their mistakes. Seeing competitors struggle to monetize, for instance, led us to embrace a freemium model — free for basic users, with tiered pricing for companies.

You can think beyond the tech

Developing a brand new product — something that’s never been sold before — is all-consuming. But, ultimately, product development is just one part of running a successful business. First-movers, in my experience, fixate on this element, while neglecting marketing, sales, and other critical functions. Our early competition really had no customer service, for instance — user complaints went unnoticed and unaddressed. So we made customer support a priority right out of the gate. We also poured time and energy into building a community of users — holding meetups and appointing product ambassadors around the world. As a second-mover, we had the luxury of creating a culture and a brand, not merely a product.

You get the thrill of the chase

As a second-mover, you benefit by having a clear, real target in your sights. Chasing down a market leader keeps your mission focused and your team aligned. For example, our initial goal was simple — to close the gap with the competition by signing up new users and winning over some of theirs. First-movers, by contrast, are forced to drive looking in the rear-view mirror. The road ahead is unclear and full of obstacles and contenders are constantly closing in from behind. This can be supremely stressful, which may explain why so many first movers end up taking early exits, preferring the safety of an acquisition to the uncertainty that lies ahead. Such was the case with CoTweet, TweetDeck, and some of the first movers in the social media management space.

If you’ve got a brilliant idea, and others around you are making headway, by all means get your product to market.

Don’t get me wrong. Timing is important. If you’ve got a brilliant idea, and others around you are making headway, by all means get your product to market. By the way, this kind of “simultaneous innovation” happens all the time — and has little to do with copying or corporate espionage. It’s just that technological and cultural conditions evolve and, suddenly, an idea like live streaming video or self-driving cars or even fidget spinners makes a lot of sense, and lots of people start chasing it.

But don’t be discouraged if you’re not the first on the scene. Research backs this up. For startups entering new markets, first movers are six times as likely to fail as “fast followers” — companies who get in on the ground floor, but aren’t necessarily pioneers. After all, being first to market usually comes down to a stroke of luck. It’s the ability to win over customers and keep them coming back over the long haul that’s the real differentiator.

Syndicated with permission from Ryan Holmes’ @invoker Medium account