This time last year, the end was approaching for Omnirobotic. Technology market conditions were deteriorating and the venture-backed startup had failed to secure Series A financing. Even after laying off a third of its staff, the Laval, QC-based company was still running dangerously low on cash.

In consultation with its board of directors, investors, creditors, and employees, Omnirobotic was considering all options, from selling to shutting down to abandoning its ambitious, capital-intensive, factory robot-training software vision.

In an interview with BetaKit, Omnirobotic co-founder and CEO Francois Simard said it took three months to accept that he was not going to be able to raise new funding to fuel the company’s recurring revenue platform strategy and half a year for Omnirobotic to secure the buy-in required to restructure and reinvent itself as a maker of autonomous industrial robots.

“We were lucky enough to have believers—employees that believed, investors that believed, creditors that believed—in the new business model, and we made that a reality.”

Francois Simard, Omnirobotic

While this pivot from an artificial intelligence (AI) software firm into a less scalable but more sustainable machine builder seemed like the best path forward for Omnirobotic, Simard acknowledged that it was still a gamble with no guarantee of paying off.

Following a “challenging and unpleasant” process, Omnirobotic had restructured by last July with the help of its largest and only secured creditor, Investissement Québec. The old Omnirobotic was shuttered and a new corporate structure with a fresh capitalization table was born.

That entity secured $500,000 CAD in equity funding from company management and some new and existing strategic investors, acquired Omnirobotic’s assets from its predecessor, and set out to reach profitability as quickly as possible.

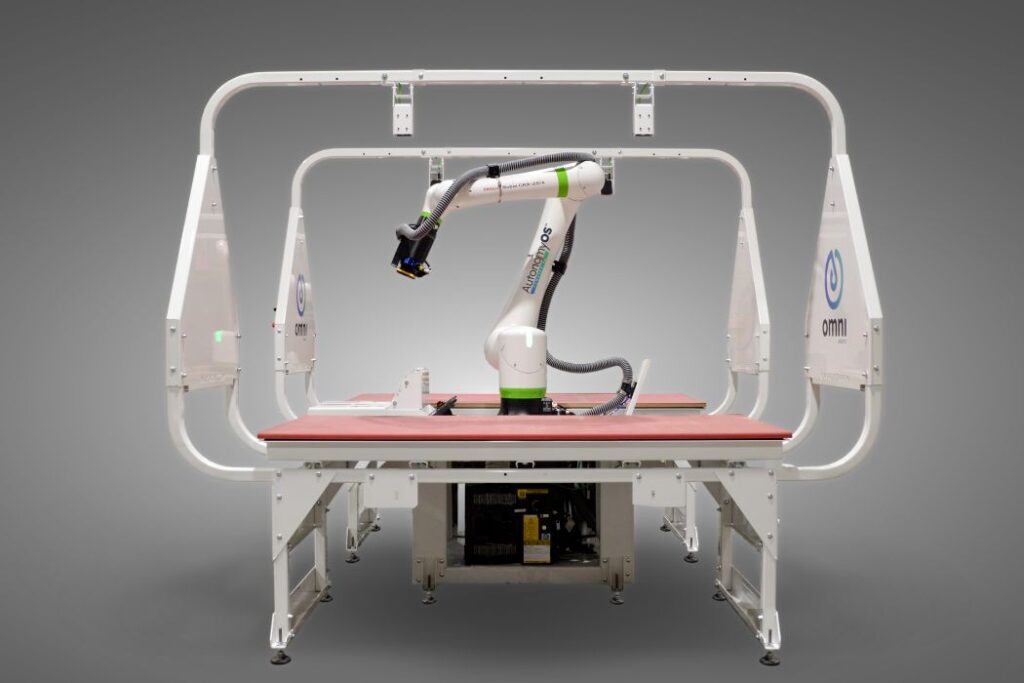

Eight months later, the plan is working. Within its first six months as a machine builder, Omnirobotic surpassed its annual sales estimates and became profitable. Today, the company’s panel sanding robots are being used across North America, where they help kitchen cabinet manufacturers with as few as six employees automate one of the hardest tasks in their shops.

“The Omnirobotic of 2024 is a totally different company,” said Simard. The new-look firm has recently moved into a new 6,500-square-foot facility in Laval to keep pace with demand, has grown its team, and expects to hit $5 million to $10 million in revenue this year with a “very healthy” debt-to-income ratio.

For his part, Simard is proud of the company’s progress to date and particularly appreciative of the folks who helped Omnirobotic turn what was an existential crisis into an opportunity to commercialize its tech in a different and less expensive fashion than initially intended.

“We were lucky enough to have believers—employees that believed, investors that believed, creditors that believed—in the new business model, and we made that a reality,” he said.

RELATED: Tiptap and Omnirobotic pursue restructuring after startups fail to raise additional funding

For Simard, the transition represents a return to his roots. “For me, it was getting back in my old shoes,” he said. “I know how to build robotic systems in general and especially autonomous robotic systems.”

In 2000, Simard launched Orus Integration, a machine vision-focused robotic integration company. Orus was acquired in 2010 by AGT Robotics, a robot welding firm, which purchased it to generate motion on never-before-seen parts. He stayed on with AGT for six years before teaming up with CTO Laurier Roy to launch Omnirobotic in 2016.

“We started Omnirobotic to do only that … 100 percent autonomous robots,” said Simard. “Robots that see, understand, and act without supervision. And that was a very ambitious goal.” Back then, the labour shortages that Omnirobotic hopes to help address were far less pronounced—today, Simard noted that they dominate the news cycle.

Initially, Omnirobotic garnered support from venture capital (VC) firms and other institutional investors to build software that customers could use to design, build, and train autonomous factory robots and pay a regular fee to use said platform to drive those robots.

Simard understood that developing such a platform and getting to the point where it could generate enough recurring revenue for Omnirobotic to become a self-sustaining business would take a lot of time and money. The CEO said he knew Omnirobotic would run a deficit every year for some time and may even be sold before breaking even.

To accomplish this goal, Omnirobotic raised about $10 million in total funding from a group that included Le Fonds de solidarité FTQ, Export Development Canada, Real Ventures, and ServiceNow-owned Element AI.

But closing a Series A round in 2022 amid the early days of the tech downturn proved impossible, and when Omnirobotic asked existing backers to inject fresh capital to fuel its continued operations or support a pivot into something more efficient but less scalable, Simard said that most—including the VCs in particular—proved unwilling to do so.

RELATED: Omnirobotic raises $6.5 million CAD as it looks to develop industrial autonomous robots

Despite this hesitation, some of Omnirobotic’s strategic investors, including the management of Génik—a Québec-based manufacturer of custom robotic equipment—remained believers, but were not interested in investing in the company as currently constructed. “I think in a way, they knew more than we do how fast we could sell those machines,” said Simard.

Simard said the firm tried to be transparent about its prospects and direction throughout this process. After exploring other options, Omnirobotic proposed becoming a machine builder itself focused on making and teaching robots to autonomously complete specific trades in segments where it could sell at least 1,000 across North America directly to end users.

Omnirobotic laid off 19 of its 29 employees in February 2023, keeping on a skeleton crew capable of serving its existing customers and supporting this new strategy, moving its equipment and remaining team to a smaller location to reduce its operating costs.

With help from Investissement Québec, four months later, a new Omnirobotic with a less onerous debt burden was established to do just that. That new entity secured $500,000 from members of the management of Omnirobotic, Génik, and Génik owner ExcelPro to fund its continuation. Through this transition, Simard claimed Omnirobotic did not miss a day of operations or lose any clients.

RELATED: Promise Robotics nets $21-million Series A to hasten home building with robots

“As commercialization of the technology took longer than anticipated, our support was needed to set up a structure that would attract new investors,” an Investissement Québec spokesperson told BetaKit. “This collaboration ensured continuity of operations and maintained the technology’s intellectual property.”

The mandate of the province’s investment arm, which has backed Omnirobotic since 2018, is “to boost the growth of Quebec companies,” the spokesperson added, noting that firms like Omnirobotic that develop tech to improve the efficiency and productivity of local manufacturers align strategically with this goal.

For his part, Génik VP of technology and innovation Patrick Gariepy told BetaKit that he believes in the AI vision and robot guidance tech that Omirobotic is developing, calling both technologies “the keys to future innovation.” He added, “We wanted to be part of [Omnirobotic] because it is also our future.” In time, Gariepy anticipates that Omnirobotic’s tech “can be and will be used” across a variety of automation solutions.

Today, Omnirobotic’s software is an internal tool: the product it is using to create the machines that the company sells. The firm designs its autonomous robots leveraging a combination of off-the-shelf and custom components constructed by subcontractors, assembling them all in-house. On a mechanical level, Simard described Omnirobotic’s tech as being “as complex as a picnic table.”

Omnirobotic builds the machine around these robots, imbuing them with 3D vision, a laser sensing system, and a brain, training them to understand what they need to do with the help of its existing AI-powered software platform—an approach he claimed brings greater efficiency.

“The cost to build the machine is less, the complexity is less, and we’re leveraging AI to compensate for mechanical errors,” said Simard. “That’s very different than the typical machine builder that will have a lot more constraint on the mechanical level because the programming is assuming a perfectly flat bed … in our machine, nothing is perfect. We’re expecting imperfection. We simply taught the robot to use their sensors to inspect themselves, align the digital twin to the physical twin, and then from there, the AI manages that.”

Now, Omnirobotic is building its machines in batches, typically 10 at a time, and selling them faster than they can make them, Simard said. Omnirobotic’s new building gives it room to assemble up to 180 per year, and the firm is presently growing at more than twice the rate it was anticipating.

RELATED: PitchBook analysts say 2023 VC funding is “pretty much shot,” long-term recovery appears likely

While Omnirobotic’s panel sanding assistant “alone can fuel the company for five years,” Simard said the company’s plan involves bringing at least one to two new machines to market per year. It is currently working on a larger version of its panel sanding assistant as well as a new robotic grinding assistant, both of which will expand its customer base to new markets.

Speaking to other entrepreneurs who might be facing similarly tough choices amid the ongoing tech downturn, Simard acknowledged that eschewing Omnirobotic’s grand software platform vision was difficult, especially since the startup had VC investors who wanted it to stick to its original mission, but said it was a necessary step for the company and its team given the dire circumstances it faced.

“You need to liberate yourself from [that] paradigm and say, ‘Okay, let’s forget about everything [else],’” he said. “What can you do to create value with the team and the tech you have right now in a very short period?”

Within its first six months as a machine builder, Omnirobotic surpassed its annual sales estimates and became profitable.

In a situation like the one Omnirobotic faced last year, he noted that time is of the essence. “If you take too long to go that route, you’re going to hit [a] wall,” said Simard.

Omnirobotic’s reinvention would not have been possible without Investissement Québec restructuring its debt to keep from draining the capital out of the new firm once new money was invested.

The same is true of the strategic investors and employees who stuck by it. Today, Simard said, Omnirobotic’s cap table resembles that of a classic manufacturer. “It’s not a company that has been built to go from round to round,” he noted. Upon request, last summer, Omnirobotic allowed its employees to invest in and become shareholders in the new company. All did, putting over $10,000 apiece in addition to that $500,000—to which Simard credits some of the firm’s work during this challenging period.

“We had an incredibly motivated team,” said Simard. “If you’re putting your own money in the business as an employee, you want that company to succeed. And that proved to be incredibly motivating for everybody.”

Feature image courtesy Omnirobotic.