Soon we’ll all be able to take the red pill.

Virtual reality is thrilling, but it is often difficult to describe, since it drops the user into a 360-degree virtual world, creating an inherently unique, immersive digital experience.

As a result of the current frenzy built up around virtual reality, many Canadian video game development studios have jumped at the chance to create software designed around the exciting emerging technology, building games and experiences for VR. But is the growing virtual reality hype train worth hitching a ride on and ready for mass consumption, or is VR another passing tech industry trend like 3D or motion controllers?

“It’s a bit precarious, actually, as the ‘wow factor’ seems to be glossing over many of the technology and content issues,” said Toronto-based Phantom Compass creative director Tony Walsh, discussing recent industry speculation often citing 2016 as the year of VR. “It’s an exciting time, because anything goes, but I feel the industry is setting consumer expectations too high.”

Creating interactive content for an in-development platform, in what is still an unproven medium, is a difficult task, and Walsh says his uncertainty regarding virtual reality’s real potential is growing, even as his development team continues to work on its first VR-enabled title, a car combat game called Auto Age: Standoff.

“Oculus recently announced the consumer model pricing, and the PC hardware requirements. It’s going to be substantially more expensive for us to properly develop and test our game — if we can even get the consumer hardware,” said Walsh, discussing the difficulties of creating software for a still-in-development platform. “I can’t even guess as to what 2016 and 2017 holds for the VR market.”

When it comes to the upcoming modern wave of modern virtual reality headsets, only a single consumer device, Samsung’s Gear VR, has actually been released. Facebook’s Oculus Rift, HTC’s Vive and Sony’s PlayStation VR, three of the first full-fledged VR headsets, are still looming on the horizon, with release dates staggered over the rest of this year.

In the context of traditional video game consoles, systems often live or die by the quality of their software, especially at launch. This is an issue VR must contend with to be successful, regardless of how promising a headset may initially seem from a technical perspective.

Impressive demos are perfect for showing off what virtual reality is capable of in short bursts, as well as introducing newcomers to the technology. It’s unclear, however, if full-fledged VR games will remain compelling after a few hours of play, once the original wow factor is gone.

There’s also the question of price, which is virtual reality’s most significant barrier going into 2016. While the cost of full-fledged VR headsets is sure to plummet over the next few years, Facebook’s Oculus Rift is currently priced at $914 CAD, and HTC’s Vive is predicted to land above the $1000 mark.

Add the cost of a powerful PC on top of this amount – an additional $1000 to $1500 – and the price of high-end VR hardware becomes untenable, especially when compared to the average cost of a modern video game console like the PlayStation 4, Xbox One, or even a standalone gaming PC.

Sony’s PlayStation VR (formerly known as Project Morpheus), which is powered by the $430 PlayStation 4, will likely be the easiest way for many people to experience full-fledged virtual reality, despite the various technical limitations, such as poor screen resolution and hardware constraints, that come with an aging console.

That said, many independent Canadian video game developers are betting virtual reality represents the future of the video game industry, and will push the medium forward in terms of innovation and immersion. VR may not become mainstream for a number of years, but working with the technology today allows developers to hitch a ride on its potential, banking on the technology’s future success.

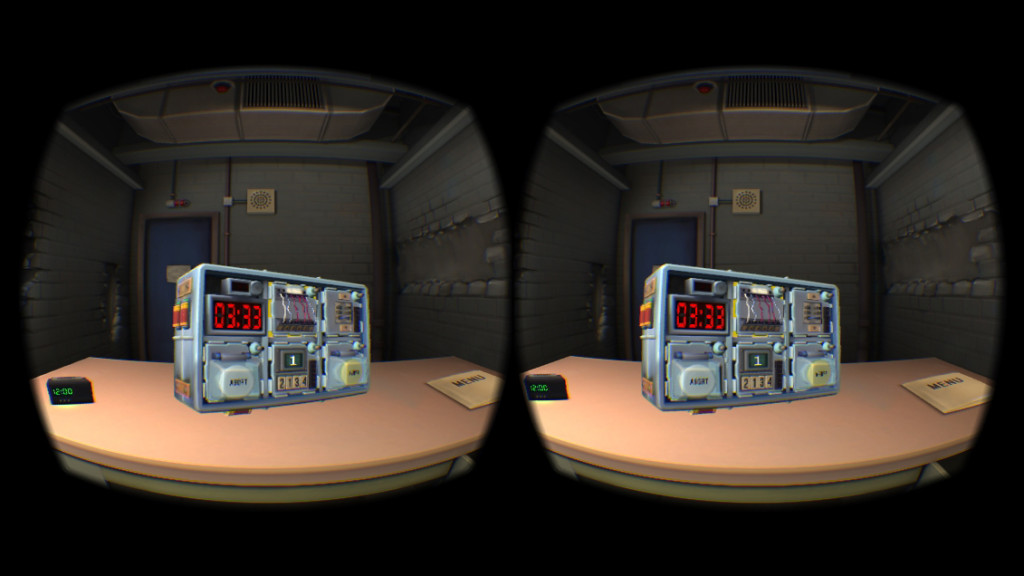

Ottawa-based Steel Crate Games’ Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes was conceived at a Global Game Jam in 2014, and has slowly evolved into one of the Oculus Rift’s marquee demos and a top-selling Gear VR title. (Samsung’s VR software is powered by Oculus.)

Despite claims virtual reality will change the way we interact with one another, few games, or apps for that matter, feature multiplayer or online social components. This is an issue Ben Kane’s studio set out to tackle with Steel Crate’s quirky bomb diffusion title.

Kane says shortly after creating a simple VR roller coaster demo and observing the crowd watching his title in action, he realized he needed to find a way to allow observers to engage in the experience.

This serves a dual purpose. First, trying VR for the first time becomes a social experience, promoting the technology in new ways; and second, it resulted in Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes becoming one of VR’s first well known multiplayer titles.

“We looked at the situation and decided to make a game based on the fact that players in VR and outside of VR saw different things. Each group would have different pieces of information and together they would solve puzzles. Bomb defusing was a scenario we came up with quickly after that and then we were off to the races,” said Kane, one of Steel Crate’s co-founders.

Kane says that despite his optimism for VR, it’s often difficult to convince casual observers of the technology’s potential, given how unproven the technology is. There is an inherent social and safety barrier that comes in the form of a pint-sized LCD panel strapped to one’s face.

“We spent much of the past year touring our game around conventions showing it to as many people as possible, because there simply doesn’t seem to be any other way to truly convey what VR is. It’s an uphill climb that virtual reality will continue to face until it can become a mainstream technology. The upside is that while it might be time-consuming to show VR to everybody, it’s remarkably effective at creating ‘believers’ once they do get that headset on,” said Kane.

Kane says that while he’s targeting the Oculus Rift with Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, the game will also make its way to the HTC Vive and PlayStation VR at some point.

Another issue many developers are experiencing with VR relates to deciding which platform to design their games for. The Oculus Rift is backed by Facebook which, compared to many other upcoming VR headsets, has a seemingly infinite amount of money and time to burn as virtual (hopefully) evolves into pop culture mainstay. Some studios however, are betting that Sony’s PlayStation VR will win the ensuing platform war, primarily because it’s powered by the PlayStation 4 console, a system that has already sold over 36 million units worldwide.

In Saleem Dabbous’ case, his studio KO_OPmode decided to bring its VR title, GNOG, to PlayStation VR because Sony offered financial support, but he doesn’t rule out the idea that the game could land on other VR platforms in the future.

Like many VR experiences, GNOG, which is also part of Double Fine Presents indie game publishing platform, is a difficult game to describe, especially since it draws inspiration from abstract titles like Hohokum and Fez.

“GNOG is the kind of game where you’re lost at first with no guidance, but through the act of play and discovery you begin to form links and uncover a subtle narrative across a puzzle. It’s also heavily musical, with the art and music being created to go together as perfectly as possible,” said Dabbous, describing his studio’s puzzle-focused colourful virtual reality title. “Each level is designed like an instrument, where through the process of going through a puzzle the soundtrack begins to form and build.”

Sarah and Colin Northway, of British Columbia-based developer Northway Games, opted to take a different approach by reviving their popular Flash game from 2008. Fantastic Contraption, an upcoming HTC Vive launch title that takes advantage of the headset’s motion-tracking cameras and gamepad. This allows the player to physically control their location and actions in the digital world.

“The [updated] Fantastic Contraption has been designed from the ground up to be a room-scale VR game. Imagine walking around a grassy island floating in the sky making a contraption the size of a horse with your hands then watching it roll out into the world. It’s a VR experience you and your friends will play for hours,” said Colin Northway, emphasizing that, similar to Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, his title also includes a social component.

Just like Walsh, Northway says he experienced a number of difficulties when it came to creating virtual reality content, even in the early concept stage. In his mind, virtual reality experiences need to make sense within the context of the technology, and forcing VR into a game where it doesn’t work – similar to what happened with 3D TV and games in the early 2010s – is a misuse of the technology’s potential.

Northway says his studio, as well as Radial Games, Fantastic Contraption’s co-developer, are aware of the inherent uncertainty stemming from working on an early VR title, but that despite early skepticism, the payoff will ultimately be worth the risk.

“We all got together and agreed that we might not make any money. That the world might not be ready for VR, that some celebrity might claim it causes brain cancer, that it will cost too much…,” said Northway, discussing how cautious he initially was about VR. “Now I’m very confident it will take off. All tech starts off expensive but the price will go down over time, and when it does Fantastic Contraption will be a ‘VR Classic’ ready for all the new players,” he concluded.

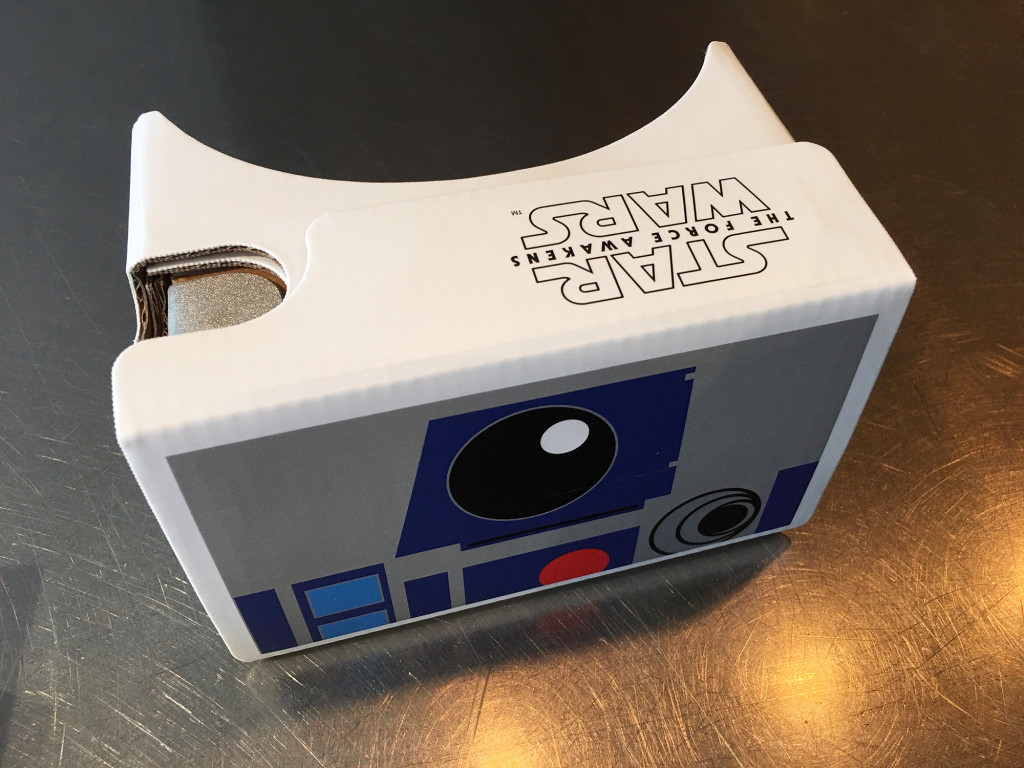

In 2016, virtual reality is expected to generate $5.1 billion USD, an increase from $660 million USD in 2015, and a substantial amount of money. But premium VR hardware such as the Oculus Rift and HTC Vive are only predicted to sell 6.6 million units in total, giving developers a small install base, as well as a limited audience, at least in the immediate future. One shining light in the category comes from mobile VR headsets like the Gear VR and Google Cardboard, which are expected to sell 27.1 million units in total in 2016.

This is why Miaomiao Games’ Whisper Dungeon landed on Google Cardboard and not upcoming high-end virtual reality headsets.

“There are more people out there that own a smartphone than Oculus. The Google Cardboard SDK works on iOS and Android. This means I can support even more users. At the time when I created the Cardboard game people were really excited about the idea of low cost VR. We just wanted to ride the wave,” said Miaomiao Games’ Macy Kuang.

For most people, cheaper, entry-level VR headsets like Google Cardboard will be the only feasible way to experience virtual reality for the next few years, at least until the cost of high-end VR hardware becomes considerably lower. Until then it’s up to early adopters to evangelize virtual reality, touting its potential to friends and family.

While it’s still too early to tell if VR is just a passing tech industry fad, many Canadian independent developers are banking on its future success and its potential to break into the mainstream.

This article was originally published on MobileSyrup.