Jeremy Bell, co-founder and CEO of Wattage, met me in a bright and airy Cossette office in Liberty Village, just a short walk away from where Teehan + Lax HQ once stood. Bell walked away from his partners at Teehan+Lax in pursuit of an idea. How do you make it easy for people to build something physical and programmable, something that’s not just another app or a website?

“The leap from the digital world to the physical world was significant.”

“We spent all this time creating digital stuff, and the purpose of Teehan + Lax Labs was to future-proof us as an agency,” Bell tells me. “A lot of our staff would come in and essentially turn around and walk back out.

“They would all come in with ideas they had in their head, but the leap from the digital world to the physical world was significant. We had Arduino, laser cutters, 3D printers, and Raspberry Pi. How could we make it easier? That’s how our idea was born: can we create digital tools to allow people express themselves, physically create something?”

Joined by Peter Nitsch, former director of Teehan + Lax Labs, and two others, Bell set out to explore the idea of making hardware drag-and-drop easy.

Can hardware go from a drag to drag-and-drop?

If you ever visited any makerspace, or for that matter any hardware startup, you know the drill. At best, you’re walking into hanging wires on the left, electronics, all kinds of parts and screens on the right. The popularity of 3D printing has made it easier to create and customize things, but the learning curve for most people is still pretty steep. With Wattage software, people can just start building.

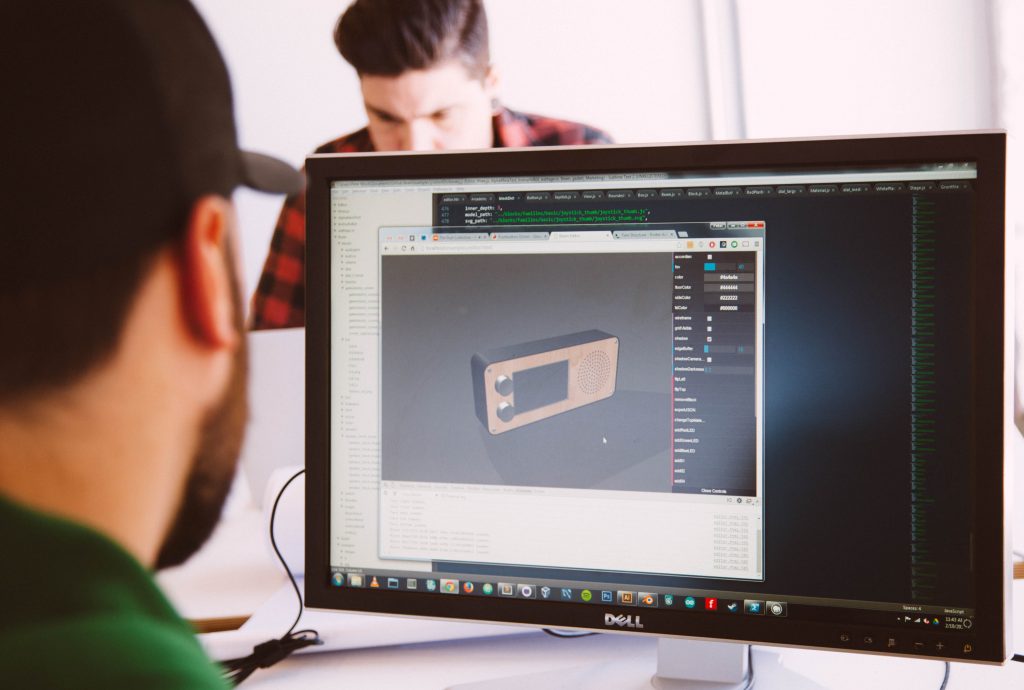

Let’s say you want to build a podcast radio. You’d start off with a box and manipulate its dimensions, change colours to make it white or black, and add various components like sliders, materials, buttons, screens, or switches. The software takes care of the right positioning of all elements, because it knows how much space they require physically, and how they need to be mounted. All of the electrical aspects, how the data is being routed, and how much power the piece will require, get abstracted away. The only thing you’ll be worrying about is what your podcast radio actually looks like.

“I believe the physical interfaces you get on the apps aren’t ideal,” Bell says before offering me a yellow gummy bear. “If you’re mixing boards, as a DJ, touch-screens just don’t work as physical interfaces with tactile controls.” The best part about making your own custom podcast radio or mixing board? Wattage will manufacture it for you.

“Wattage is essentially an abstraction layer above digital fabrication tools and electronics,” says Bell. “You should be focused on what you want to do, and not to worry about the electronics on the inside, how to mount these things, how much tolerance they need, and all the wiring – our software takes care of all that.”

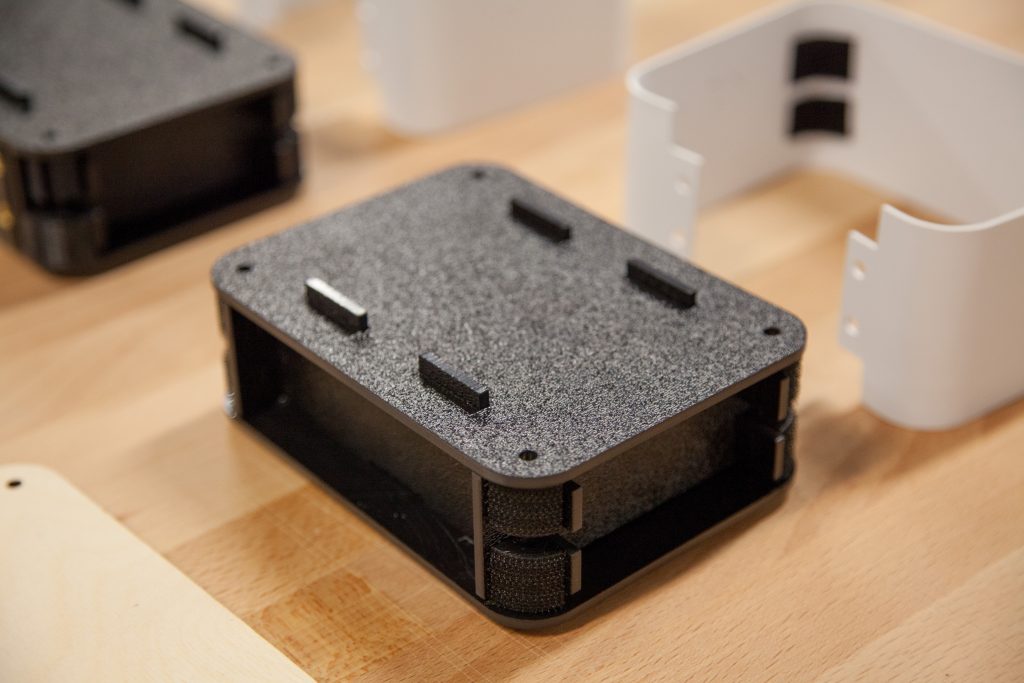

While the software side of things sounds complex enough, Bell gets just as excited talking about manufacturing all these physical things that people will create. “We’re using laser cutters predominantly now for manufacturing. We used 3D printing to build prototypes, and we found it was absurdly slow, expensive to make, and the material doesn’t hold up great. It had this texture-y feel I didn’t love. Laser cutters get you closer to the final product you could proudly put on your desk, and let you play with plastics, leather, paper, all kinds of materials. We’re going to stick to plastics and woods to start. All the electronics inside are all custom to some extent, with Arduino-based programming.”

Modular manufacturing

Bell thinks that with Wattage software, people without any knowledge of electronics might create the kinds of things that otherwise might not have existed because it made no sense to mass-manufacture them. “The whole system we have now is about mass-production. We want to let you make one thing, make it very easy to connect to the internet, and send and transmit data, whether it’s door knobs, radios, or lamps.”

The democratization of hardware manufacturing gets more exciting when you think through the way digital tools tend to build on each other. For example, you hardly even need to write your own code anymore, because someone somewhere has already written the server functionality you need, or designed some of the graphic elements you want to use; modular digital blocks of code can be mixed and matched to make decent apps. Bell thinks the physical world of things is headed in a similar direction, with basic modular building blocks being defined, assembled, and remixed in new ways, with neat “custom” building blocks thrown in. Wattage software will allow people to create and re-mix those niche, custom components.

“The idea of customizing your shoes with Nike, Google’s project Ara, it’s all about letting people create something that’s highly personal for them,” Bell tells me. “We looked at studies about customization and assembly, and when someone has the ability to personalize something and make it their own, they are far more likely to spend more money on it and derive more value from it. Their affinity for the product is significantly higher; people want to show it to others and tell their friends. There’s something about making and assembling things, you just own it in a different kind of way.”

It’s the kind of change that feels inevitable. I never knew I wanted to make a podcast radio. Suddenly, the very idea of going to the store and buying a mass-produced piece of equipment feels ancient, odd. If Wattage can make physical objects more mouldable, modular, accessible, and custom, I’ll be a bunch of steps closer to making my very own podcast radio a reality. Knobs and all.