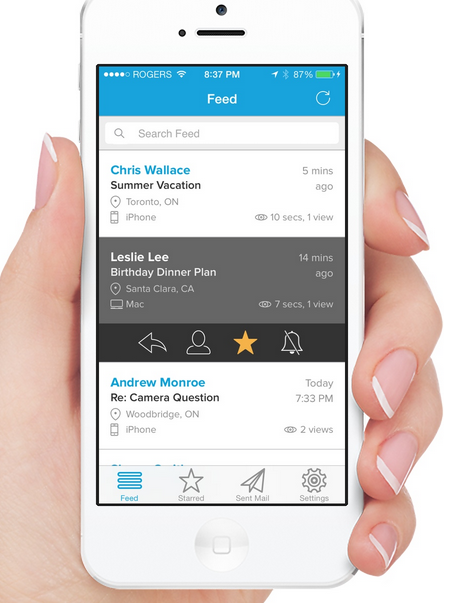

An interesting article was published two weeks ago in the Globe and Mail, on a new Toronto startup called MailTracker. The startup has built an app that currently supports email accounts, allowing a user to know how many times and when an email recipient has opened their message.

It currently supports Gmail, Google Apps Business, iCloud, Yahoo!, Outlook.com/Hotmail, custom IMAP/SMTP accounts.

Apps like MailTracker, as well as Toronto’s MailChimp, are primarily targeted towards sales people, or at least that’s what the startups will proclaim. In reality, it’s for anyone who wants to have “actionable insight” about those opening their emails.

The process is pretty simple, as the Globe’s Ivor Tossell pointed out. These apps simply attach an image property to an email a user sends, also known as a “unique identifier”. “When the e-mail gets opened, the recipient’s computer needs to fetch the tiny image, by following the link back to the server it’s stored on. That server, in turn, takes careful notes. If a computer comes looking for an image with a certain name – bingo, it knows the corresponding e-mail has been opened,” wrote Tossell.

MailTracker’s cofounder Chris Nguyen told the Globe that “It’s fun, because it’s so simple, but so valuable in the right use cases for consumer,” and that “we took the same technology that marketers have been using for the last 20 years, and decided that we’d apply it to the consumer market.” Their service runs for $4.99 a month after an initial free period of two months.

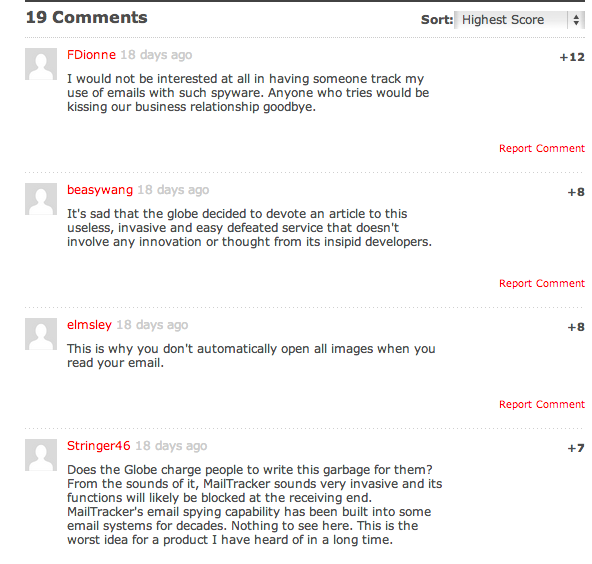

Granted, the Globe and Mail’s readership is a bit different than BetaKit’s, and maybe a bit less knowledgable about just how much the Internet knows about you and I. Nevertheless, I found the comments interesting.

Largely, readers denounced both the Globe for publishing the article, and the startup’s product as “wankerism”, “spyware”, “an invasion of privacy,” “invasive,” and “multiple violations” of “Canadian privacy laws.”

A few things: first, users can choose to turn their images off, deflecting most of the insight that others can gain from apps like MailTracker. Second thing: who cares?

I like to think back to a conversation with Kiwi Wearables cofounder Ashley Beattie at SXSW 2014. Beattie, who was formerly employed within Canada’s national defence sector, put it bluntly to me: while concerns revolving around the NSA, personal privacy and how much the state knows about its citizens are valid and necessary, most people don’t realize that the sheer amount of information available on individuals mostly renders ordinary people of little to no value to those working within defence. Translation: there’s so much information out there to sift through that defence agencies likely don’t care about the average Joe.

Google, Amazon, Facebook, Twitter and many others have compiled tons of information about people, and of course it’s unnerving, weird and scary. On the other hand, ten suited men are probably not sitting around a table in an underground compound in Arizona watching video of your latest trip to WholeFoods.

It shouldn’t come as big surprise that apps like MailTracker and MailChimp are out there, can gain this type of information about individuals.

So someone knows that you opened their email 53 times before answering it. Big whoop.

On that note, I did actually try MailChimp for about four months.

For those four months it was pretty cool and insightful to know how many times and when people were answering my emails. Sure, it can be seen as a helpful tool in targeting sales leads. And admittedly yes, it does lead to discussions on the safety of data about individuals.

One guy actually did look at my email 53 times before answering it, which I found incredibly amusing. But the truth is, most people took between two and four glances at an email before answering. Likely they saw the email on the streetcar while checking their iPhone. Once they had time later on in the day, sitting in front of their screen, they could formulate an answer. Nothing really surprising.

Marketers have been finding ways to dig up information about consumers for decades, and now a few apps are letting some of us use it for business or personal reasons. But it’s not the end of the world if someone knows how many times you looked at their email.

“They’re worth having in legal fields and other mission-critial ‘you’ve been served’ kinda areas, but just about everywhere else, these tools come off as disingenuous,” said Beattie.