Where governments step in, entrepreneurship tends to die.

In the early days of co-founding GoFetch, I have learned that traditional commerce is only at the beginning of a dramatic change led by the upstart of companies leveraging the sharing economy. Other sharing economy companies like Airbnb and Uber blur the lines between our personal and professional lives, creating uncertain territory for business owners, consumers and governments. For now, the sharing economy is a highly unregulated part of business. Eventually, that could change. But what regulation looks like — as well as who actually creates and enforces regulations — is also bound to change.

Let’s look at three real-world examples of how governments are trying to influence regulation in the fast-paced world of online marketplaces.

Taxing Airbnb hosts and why it won’t fix the rental problems cities are facing

Airbnb is notorious for fighting government regulations in the cities they operate in. Airbnb allows many people to supplement their income and pay their bills, being incredibly attractive in expensive cities like San Francisco and Vancouver. Regulators believe in order to decrease rental rates and increase vacancy rates, making their respective cities more ‘liveable’, the need to tax hosts on Airbnb – this is simply flawed thinking.

For instance, in Vancouver, where GoFetch is headquartered and Uber is banned, there are about 5,000 Airbnb listings. City permit red tape is holding up the development of an astronomically larger amount than 5,000 housing units in Vancouver. Strata by-laws already allow local communities to enforce rules such as the frequency of rental allowed within their building and fine/enforce as they deem appropriate within the boundaries of the law.

Airbnb distributes tourist dollars more evenly among city residents versus a couple of hotel corporations receiving the majority of the benefit. City residents who use Airbnb generally do not pay the city a hotel tax as hotels do. Taxing Airbnb units like hotels are taxed would effectively be a tax increase on the residents of cities they are hosts in. In theory, this money could be funneled into affordable housing initiatives (assuming priority). There is a highly limited supply of hotel and short term housing in Vancouver and Airbnb is meeting that need. Being an attractive tourist destination is tremendously beneficial to the local economy and Airbnb is a major part of that.

Why Uber really merged with Didi

Last week, Uber announced it was selling its operation in China to a major rival ride-sharing company, Didi Chuxing. The merger presents many positives for Uber, however I still think Uber leaving China is not because of the head-butting with their rivals but because of head-butting with the state. At first entry into China, Uber needed to change its core product to adhere to payment regulations and mapping services. Uber added Alipay so Chinese customers could actually sign up for the service and partnered with Baidu so they could leverage their mapping tech (Google Maps is notoriously inaccurate in China).

In the end, it was not because of Didi that Uber needed to leave China, it was the growing national regulations – regulations that were being written while Didi and Uber were in merger talks.

Let’s take a deeper look:

- On 28 July, China announces new regulations for cab-hailing services.

- 48 working hours later, Uber decides to sell out its Chinese business to Didi Chuxing to create a cab-hailing company with over 90% market share.

I don’t believe this is a coincidence.

Assuming these events are related, then a government facilitated the creation of a monopoly in China.

China has demonstrated that it will not allow foreign companies to control its vital assets — in this case, the asset is potentially their online ecosystem. This is not new for western tech giants: eBay, Google, Facebook, Yahoo, the list goes on.

And why not? What China has essentially done is that it has created a giant utility out of Didi-Uber, a near monopoly, highly regulated—yet driven by the profit margin.

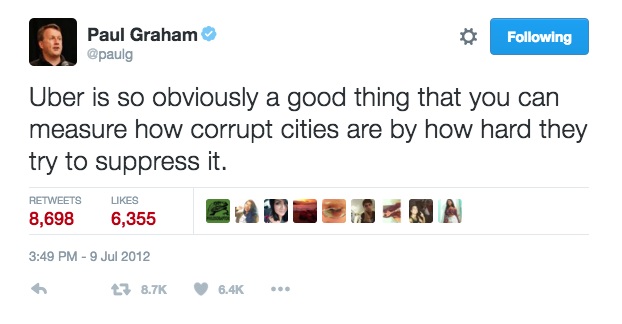

Perhaps one of the most successful VCs, Paul Graham, can summarize better than me:

Going forward, Uber can now save $1 billion per year (their reported Chinese operating costs), focus on new markets such as India (where more regulatory issues face them), and answer less questions surrounding profitability (I’m assuming they are profitable now in most of the US markets). In selling their operations to China, Uber gets to leave China in good hands and at a good price.

Thousands of users, zero employees

Personally, I look at the above illustrations as a macro-example of what will be a long and hard war – not only for Uber and Airbnb, but every high-growth startup innovating in a traditional marketplace that has never seen massive disruption, very similar to what GoFetch is doing to the pet services category.

Watching the big battles that Uber and Airbnb have faced so far, we see a group of innovative entrepreneurs come along offering a new service that breaks old rules, ignoring the traditional rules until they re-write them; and governments and traditional corporations attempt to strangle innovation and shut down the new disruption.

As an entrepreneur myself, I believe this is a mindset that marketplaces can follow for a less bumpy road in the future. It’s the way that marketplace startups regulate themselves.

Sharing economy startups might offer innovative approaches to not only their own regulation challenges, but to unresolved regulation challenges that predate their rise.

In sum, the main goal of marketplaces like Airbnb and GoFetch is to create a regulated community of strangers to do business with each other, quickly, and at scale. Because of the vast amount of consumer data that marketplaces receive, we have opened the doors to collaborate on an agreement with regulators. Here’s how: first, regulators and government need to be open to new models and disruption of traditional categories such as travel and competition, opening the door to innovation, testing, and learning for entrepreneurs and startups.

In exchange for this, marketplace companies need to share their untampered user data with government regulators, just as their customers do with them. This gives us the freedom to experience the obvious benefits of marketplace startups, while giving governments better understanding of the real positives that come because of them.

Put differently, sharing economy startups might offer innovative approaches to not only their own regulation challenges, but to unresolved regulation challenges that predate their rise.

Final thoughts

Everyone from venture capitalists to consumers realize that the sharing economy is too big an opportunity to miss. Governments also see that it’s too risky to ignore. Like all major disruptions, marketplace startups are challenging regulatory incumbents with new business models and new ways of engaging customers. Existing regulators will need to embrace companies like Uber and Airbnb and transform their boundaries to meet consumer demand, or find themselves disrupted by those who do embrace this shift.