Canada receives global attention for its high-quality artificial intelligence talent — specifically, the talent coming out of Toronto and Montreal. The country’s two biggest cities are home to the Vector Institute and MILA, respectively, and deep learning researchers Geoffrey Hinton and Yoshua Bengio have been very public about training the next generation of AI talent in their respective dominions.

But what if we told you that the next global AI hub will be situated in the heart of Canada’s oil and gas sector?

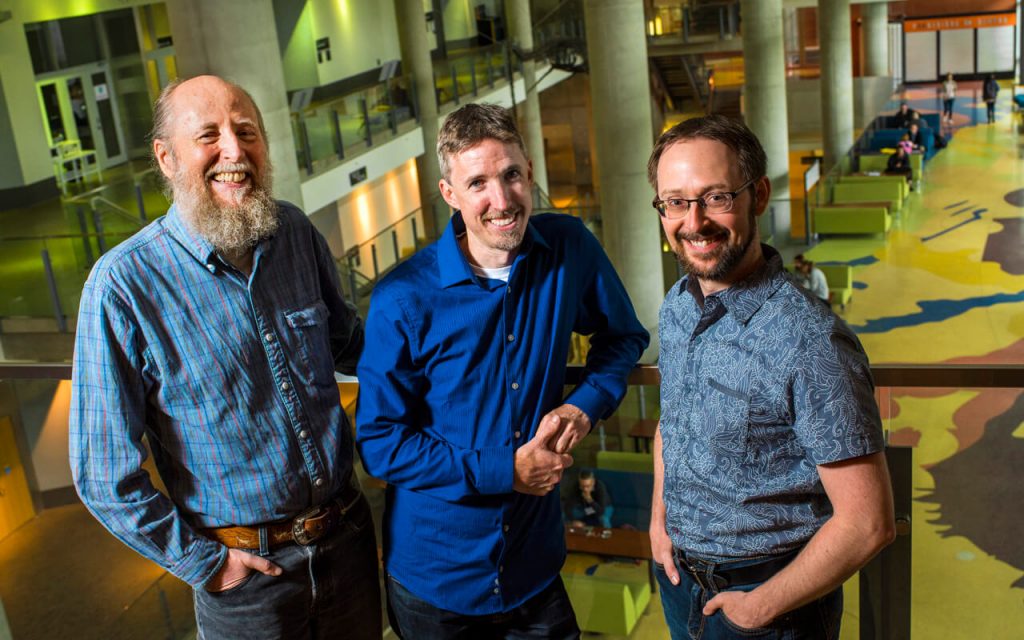

Cory Janssen expects big things for Alberta’s tech ecosystem.

Janssen knows a thing or two about big tech stories. He co-founded Investopedia in 1999, growing it into one of the largest websites for investor education before selling it to Forbes Media in 2007. Janssen then went on to found Janalta Interactive, a publisher of educational content in industries like information technology and fitness.

It was at Janalta — working to automate content creation with natural language processing — that he realized the potential of his province’s AI research talent.

That spurred him to co-found AltaML, which connects AI researchers with giants in health, energy, and financial services to develop AI-based solutions to their challenges. Despite only being a year old, it already has multinationals like Boeringher Ingelheim and PCL Construction in its roster.

“We have the start of what is, hopefully, the next big story in Canada,” said Janssen.

Janssen is one of several Alberta technologists who is helping to turn the oil and gas heart of Canada into an AI powerhouse. The province ranks third in the world for AI research, and boasts a nearly 20-year history of machine learning research and burgeoning talent eager to build startups in Alberta.

The ingredients are all here, said Janssen. Now it’s time to cook.

IT WAS ALL FUN AND GAMES

The story of Alberta AI starts on April 1, 1964, with the opening of the University of Alberta’s department of computing science. Researchers such as Randy Goebel would graduate from the department and set the foundation for early work on the science of natural language processing and AI in the 80s, the latter of which took the form of studying games like chess.

By the ‘90s, however, several ‘AI winters’ — periods of funding constraints for research and lack of press interest to generate public excitement — inhibited the discoveries coming out of the university.

“The symptoms of the winter are more that industries [that] bought into the idea that expert systems could help them found that it was way too expensive to implement,” said Goebel, now a U of A professor and principal investigator at the Alberta Machine Intelligence Institute (Amii). “If you scale up, it costs a lot to have you and me write down processes for chemistry, for example.”

“The rest of the country doesn’t realize that things here suck. The silver lining is that people are saying, we can’t go through it again and we can’t be on this resource boom and bust cycle.”

– Cory Janssen, CEO of AltaML

By 2002, Alberta’s researchers had managed to convince the provincial government to make a forward-looking investment of $2 million CAD over five years for the Alberta Innovates Centre for Machine Learning. The first sign of Alberta’s AI return on investment came in 2007, when a team of researchers — led by University of Alberta professor Jonathan Schaeffer — solved checkers, a game AI researchers around the world had been trying to crack since 1989. Schaeffer and his team were able to correctly predict game outcomes despite checkers’ 500 billion possible positions.

Amii began to attract researchers from around the world, including, notably, Rich Sutton, who is considered a pioneer in reinforcement learning. In 2003, the year the United States declared war on Iraq, the Ohio native, unhappy with the politics of his home country, decided to move to Edmonton to continue his machine learning research.

Sutton would become key in bringing the other piece of the AI puzzle — corporate partners — to Alberta. But corporate support wouldn’t truly arrive for another decade; in the meantime, Sutton would work among professors like Michael Bowling, who has designed some of the best AI-based poker-playing programs, and train the next generation of talent at Edmonton’s U of A, now the epicentre of AI talent in the province.

ALBERTA’S BET ON REINFORCEMENT LEARNING

When most people use the term artificial intelligence they’re likely referring to deep learning, a form of AI that uses labelled data to find patterns (for example, analyzing 10 million pictures of animals before building a mechanism to determine the visual difference between a cat and a weasel). Breakthroughs in deep learning from Hinton, Bengio, and Yann LeCunn form the basis of modern image and voice recognition, language translation, and computer vision.

Alberta’s expertise is in reinforcement learning, a more general framework for AI that can continue to learn during normal operation — a key limitation of deep learning. Thanks to the province’s research expertise in game playing — which provides the foundation for more generalized problems — researchers in the province think they’re sitting on the next big thing.

“Choose an area to work in, place your bets, and then that may become important or not,” said Sutton. “I feel comfortable having placed our bet in reinforcement learning, which will be more important for AI in years to come.”

In 2016, researchers who got their start at the U of A showed off the potential of reinforcement learning on the world stage. PhD grad David Silver and former U of A postdoctoral fellow Aja Huang developed a program, AlphaGo, that beat the world’s best player of Go, a thousand-year-old Chinese game considered one of the most challenging for AI to beat.

“It’s extremely powerful because it’s such a general framework and it’s extremely difficult,” Anna Koop, senior scientific advisor at Amii, said of reinforcement learning.

“When the deep revolution [happened] these tools ended up being successful, which is a combination of the software development, the hardware supporting it and the data being available. Alberta was strongly positioned with a strong and broad team, and the government kept funding it all that time.”

THE NEW OIL

It’s only in the last several years that industry and academia have started to converge in Alberta, paving the way for real-world applications of AI research.

In 2015, the provincial government created the Ministry for Economic Development and Trade with the goal of diversifying Alberta’s economy to counteract collapsing oil prices. Within its first economic development agency since 2006, the province created the Alberta Innovates body — which funds Amii — and tasked it with finding research applications in health and energy research.

“The rest of the country doesn’t realize that things here suck,” said Janssen. “Toronto’s booming, Vancouver is booming, Montreal is awesome. We’re in year four of a really, really bad economy. The silver lining is that people are saying, we can’t go through it again and we can’t be on this resource boom and bust cycle, we’ve got to diversify and get our tech ecosystem going so we’re not in this situation in 10 years.”

“What’s been clearly demonstrated is that cities can’t be contained within a box or false boundaries.”

– Cheryll Watson, VP of Innovate Edmonton

Amii was asked to expand its health-care research to be eligible for funding, so the organization added health and biosystems to its portfolio, giving it another five-year window of financial support, Goebel said.

Other organizations have stepped up to this new challenge from the government. Reg Joseph, CEO of Health City in Edmonton, is using his nonprofit as a connector between tech companies and multinationals to address local health problems. As the home of 50 percent of the province’s life sciences companies, with 4.3 million people all under one health authority, and an open data portal, Edmonton is a strong test bed for new technologies.

But connecting the tech industry with clinicians who work with valuable data is a unique challenge. Health City was the driver of connecting AltaML and Boehringer Ingelheim Canada to develop a tool that predicts how aging affects health.

“We’ve brought industry in to help the clinicians,” said Joseph.

Local tech companies have also created jobs for grads who would have otherwise pursued opportunities outside the province. In 2017, Google’s DeepMind opened its first international office in Edmonton. Sutton, who has been an advisor to DeepMind since 2010, wanted to stay in the city, and convinced the giant to tap into the talent that already existed.

Alongside Toronto’s Vector Institute and Montreal’s MILA, Amii also became an official part of the federal government’s $125-million Pan-Canadian AI Strategy. Deepmind choosing Edmonton was a major proof point for the city, according to CIFAR chair Elissa Strome, who leads funding for the Pan-Canadian AI strategy.

“We were looking for places where there was already a deep ecosystem that was under development and being built, and a real strength we wanted to capitalize on and expand on,” said Strome, noting Edmonton’s strength in reinforcement learning. “Toronto, Montreal, and Edmonton were the natural places to identify not-for-profit research institutes.”

The Royal Bank of Canada also chose to make Edmonton its first Canadian base for RBC Research (today’s Borealis AI) outside of its Toronto headquarters in 2017. For researchers who want to stay in the province, it’s a valuable source of work.

“It’s my hypothesis that U of A was able to push the boundaries of reinforcement learning because the research groups there were so tight with each other and collaborated so well that they didn’t get distracted by the rest of the deep learning woes in the rest of the country,” said Foteini Agrafioti, RBC’s chief science officer and the head of Borealis AI, who added that RBC chose to set up in Edmonton within a month of first visiting.

Of course, it’s nearly impossible for Alberta to abandon oil and gas completely. But with AI’s capacity to produce predictive insights from large volumes of data, the energy sector is set to be one of the biggest beneficiaries of AI. The World Economic Forum estimates the digitization of the industry could unlock $1.6 trillion USD in value globally.

A TALE OF TWO CITIES: THE EDMONTON-CALGARY CORRIDOR

Home to Amii, Edmonton is the base for Alberta’s AI talent, while most of the energy sector have headquarters in Calgary; of 118 head offices in the city, two-thirds are of oil and gas companies.

With its proliferation of high net-worth individuals, Calgary is often thought of as the money town where entrepreneurs from Edmonton can raise funding.

In June, a working group of entrepreneurs and economic development corporations from the two cities — who have, until now, enjoyed a friendly rivalry — got together to discuss the early stages of building closer connections between Calgary and Edmonton. Like the Toronto-Waterloo corridor, the goal is to allow startups and mentors between both cities to work together more easily and better advocate for the local tech ecosystems. Ninety percent of tech talent in the province is concentrated between the two.

“When we compare ourselves to other places, we’ve got significant research strengths, but what we haven’t seen is startups spinning out that are taking advantage of that knowledge created, and we think one of the reasons is that the cities haven’t been connected,” said Terry Rock, CEO and president of Platform Calgary, which supports local startups with access to workspace and programming.

At the heart of Alberta’s plans to build a tech corridor lies the need for an AI accelerator. In a document from June’s meeting obtained by BetaKit, the working group highlights how an AI accelerator, which doesn’t exist in the province, could be a permanent way to support the burgeoning sector.

“We consistently rank as one of the top centres in the world for artificial intelligence and machine learning research,” the document reads. “Yet, despite our strong potential, we are far from generating the number of fast scaling companies expected from an ecosystem in our position.”

“What’s been clearly demonstrated is that cities can’t be contained within a box or false boundaries,” said Cheryll Watson, vice president of Innovate Edmonton, and co-chair of the AB Innovation Corridor Working Group alongside Rock.

Tiffany Linke-Boyko, CEO of Startup Edmonton, was among those who participated in the June meeting with the working group. Startup Edmonton, which organizes programming and workshops to help entrepreneurs with their businesses, has hosted events like DemoCamp with Startup Calgary to bring the two ecosystems closer together.

Having an accelerator would create more opportunities for companies at different stages of growth, she noted, and currently organizations like Creative Destruction Lab’s hub in Calgary are working closely with Edmonton startups to build connections between the two cities.

However, Startup Edmonton’s CEO also said that more people in the Alberta tech ecosystem are thinking about how to build programs that help startups on both sides.

“We’re quite small on a global scale, but we each bring very unique things,” said Linke-Boyko. “If we can join together and really help move the needle together, versus separately, I think we have more of a chance to make a larger impact.”

GROWING PAINS

While the local tech community has the right sense of urgency and ambition, it’s still in the early-stage — and there are challenges to overcome. After the recent provincial election brought the United Conservative Party to power, funding for innovation programs is up in the air.

Many in the community are questioning whether the $100 million CAD promised to AI companies by the previous government will actually come to life, and Alberta Innovates — the body that deploys funding for innovation programs, including Amii — recently suspended funding for entrepreneurs in July before reopening some programs a month later.

“We still don’t know how much money will be tabled in the budget in September, but we’ve been working with government for many years and [talking about] how crucial it is,” said Osmar Zaïane, the scientific director of Amii. “We are hoping that money will still be there and we will continue our program, so we will not scale back. We’ll continue with whatever we get.”

“When I moved to Edmonton, I loved it. It was the place I want to call home and I want to stay.”

– Dornoosh Zonoobi, CEO of MEDO.AI

At the same time, entrepreneurs must overcome the hurdles of a burgeoning ecosystem: finding mentors who can provide guidance to the next generation, as well as new sources of capital.

“When we started the Alberta Enterprise Corporation, one of the gaps we saw was there wasn’t a lot of tech executives who can give back to the startup community,” said Kristina Williams, CEO of the Alberta Enterprise Corporation.

For entrepreneurs like Dornoosh Zonoobi, the lack of people in Edmonton who have been there and done that pushed her to incorporate and raise initial funding for her startup in Singapore, where she spent 10 years in school.

Her startup, MEDO.AI, develops software that makes it easier to diagnose medical images. “I had more connections in Singapore, and…I had more examples of my friends who turned research into business. That was very encouraging,” said Zonoobi.

Despite this, she decided to stay and live in Edmonton. For Zonoobi, the best part of Edmonton is its tight-knit community — everyone is willing to help, she said — and the fact that it’s not too big and not too small.

“When I moved to Edmonton, I loved it. It was the place I want to call home and I want to stay,” said Zonoobi. “I don’t think it’s biased, but it’s one of the best places in the world to have a startup in healthcare and AI.”

AI Nation is proudly brought to you by Microsoft for Startups.

For AI companies looking to build their first application, land their first customers, or scale to a million users, Microsoft for Startups is here to help.