A few years ago, Sam Molyneux was finally finishing up a research paper he had spent three years working on at Princess Margaret Hospital. But when it came time to be submit, he found out that his research had already been scooped and published six months ago. “We realized that this problem is rampant in the science community. Everyone is unaware of what’s going on unless you’re spending a significant portion of your day just looking at the horizon,” said his sister Amy Molyneux.

The Molyneux siblings are the founders of Meta, formerly known as ScienceScape. Since 1809, 25 million biomedical research papers have been published, while the Internet has made it easier than ever to continue publishing — which also means that scientists struggle to make sense of the information. Meta’s publication-agnostic big data platform uses machine learning to organize the information in those papers and deliver it to different industries within science depending on their interest.

“In talking to various partners and the government within publishing, we realized that everyone was suffering from the same problem which is information overload, across industries it’s just gotten past the point of human scale,” said chief marketing officer Jeff MacGregor. “Meta was launched not only to help the research industry, but to reconnect the broken ecosystem across science.”

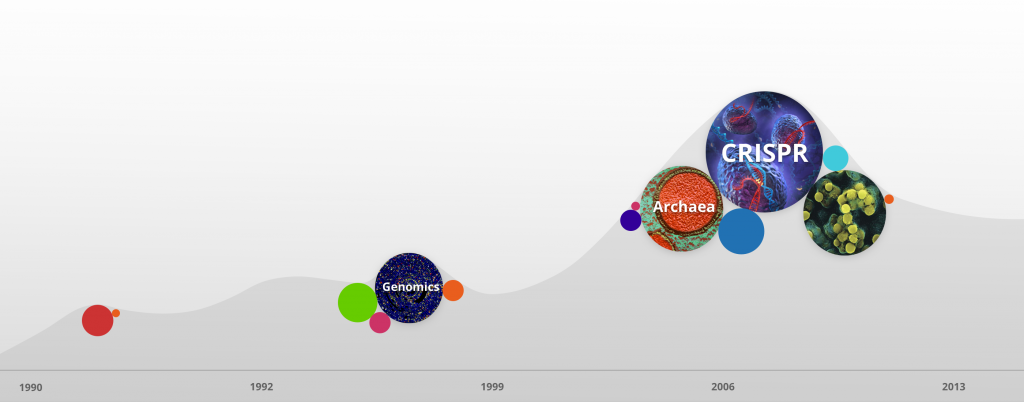

The goal is to make relevant information more discoverable, and the company is also working on algorithms that predict which technologies are going to emerge in the future. To achieve this goal, Meta acquired the technology of SRI International, a research centre based in California — and the minds behind Apple’s Siri — to facilitate early detection of scientific and technological advances years in advance.

“Imagine if you were a major funder of grants and you’re trying to figure out where to put your research dollars if you know something is going to be big ahead of time. you can deploy capital and you can actually accelerate that technology,” said Amy, who is now the executive vice president.

It’s tough to find a team as dedicated as Meta, which has been working on perfecting the algorithms behind it over the last few years. When the company was still ScienceScape, Amy spent six months living in Siberia to develop the technology there, and Amy quit her job to work on its early mechanisms.

“I saw this as one of the last great challenges online where technology hadn’t quite scaled to meet challenges of massive industry, and I either naively or bravely said that I can do this,” Amy said.

The company currently has about 30 partnerships with publishers that give Meta access to all of its historical data, with the value exchange being that information will be more discoverable to researchers.

Meta is a company that’s very much building for the future — Amy acknowledges that with such a forward-thinking vision, the company couldn’t have existed with the technology of five years ago.

“Most processes have to be mature. We can’t get away with a rinky-dink data product. We needed to wait for the field to evolve and actually wait for the costs to come down,” she said. “They have now. Today, you end up looking at the maturity of data science as a field and approach and the cost of cloud computing and you realize that you’ve got this incredible opportunity. It’s kind of the right place and the right time and we feel lucky to be taking advantage.”