It’s clear now that the COVID-19 pandemic has been one of the most significant catalysts for digital transformation this decade. Recent studies show that 97 percent of enterprise decision-makers feel the pandemic sped their organization’s digital transformation.

But what about those organizations that were already transforming? How did COVID-19 impact those projects?

This is precisely what happened with one of the largest pension funds in Canada, responsible for the pensions of thousands of working and retired teachers. When the technology powering the fund finally reached its limits, the organization faced a complete rebuild of both the front-end portal and the complex financial calculations that powered it. Thus began a digital transformation project spanning five years in a complex, highly-regulated, and security-driven environment where mistakes were not an option.

BetaKit spoke with the Jonah Group, the enterprise software developer chosen to lead the transformation about managing that process and what was required to complete the project during a global pandemic.

Rebuilding Union Station next to Union Station

The pension platform had specific requirements from a variety of stakeholders. For retired teachers, it had to display pension totals and handle disbursements. For the thousands of working teachers it represents, the dashboard needed to calculate complicated pension equations, taking into account working years, seniority, education, and other factors. On the backend, the database needed to be easily auditable and maintain a constant connection with the front-end system.

Transforming the pension platform was “building a new train station while ensuring the old one still functioned at full capacity.”

A project of this scale created additional considerations. The digital transformation was prompted by a legacy technology platform that had neared “the end of its useful life,” as Jonah Group co-founder Jeremy Chan put it. But with over $200 billion in net assets representing the retirement savings of over 300,000 people and their families, the pension fund couldn’t afford to simply take the system offline while building a new one. Further, the legacy codebase contained millions of lines of code, leaving no easy way to update the system – it would have to be rebuilt piece by piece.

Chan likened the project to “building a new train station while ensuring the old one still functioned at full capacity.” The team not only had to ensure that the new switches, systems, and tracks operated like the old ones, they also had to connect the two ‘stations’ at the end, slowly transitioning customers to the new platform without issue.

Transformation on a spectrum

Even with a working model to guide its efforts, Jonah Group couldn’t begin the project without first establishing not only what, but how the company would build. ‘Just like the old version, only better’ doesn’t quite cut it.

Most organizations are likely to ask for that exact thing, however. While this intention is usually true, it belies the true nature of quality. “Quality runs on a spectrum, not a binary,” Chan said. While it’s easy to think of work as either good or bad, the reality is far more fluid, with each decision a balance of needs, costs, and time.

“The question is about, ‘what is the impact’?” said Chan. “First, you counsel the client and make sure they understand the notion that there’s no such thing as a perfect system.”

For large-scale projects in which the results of your decisions won’t be known for years, it helps to set requirements. For this particular transformation project, one area in which it could not compromise was the feature set. The organization’s platform handled information critical to the financial lives of hundreds of thousands, so feature parity was a must. Balancing the spectrum, then came down to the question of system automation: how much human oversight was necessary to make the systems work, and what issues might require human remediation?

To lock in the client’s priorities and create a development roadmap, Jonah Group implemented a priority system for analyzing new features. If it’s a feature that can never go wrong, it’s a Level One. If it’s a feature that should be added or fixed based on feedback loops and customer requests, assign it to Level Two. If the feature is a non-critical “nice to have,” it’s in the backlog at Level Three.

“In a resource-constrained environment,” Chan said, “if an end-user doesn’t care about an issue, you shouldn’t spend money fixing it.” In other words, don’t line the station with gold if the passengers only care that the trains run on time.

Powered by trust

All the prioritization workflows and feature scoping in the world won’t save a multi-year project without trust. Matthew Solo, Senior Project Manager at Jonah Group, said the team wouldn’t have been able to do any work if they didn’t first focus on “establishing knowledge and process” both of how the legacy pension system operated but also how the pension team worked.

To build trust in the early days, Jonah Group and the pension fund co-located their teams and focused on team-building activities.

“Developers sitting beside testers,” Solo said. “Our team sitting beside their team. All learning, understanding requirements, making choices — all as we go along.”

While the team eventually shifted from co-locating full-time to having weekly check-ins, the early trust built proved critical. Chan noted that one thing many people don’t understand about digital transformation projects is the invisible costs. Teams, he said, only spend about 25-30 percent of their time coding or building software; the rest is spent on brainstorming, client management, analysis, design, meetings, etc. A common result is that projects can hit budget overruns in the early days as the teams get used to working with one another. This is exactly what happened with the pension project.

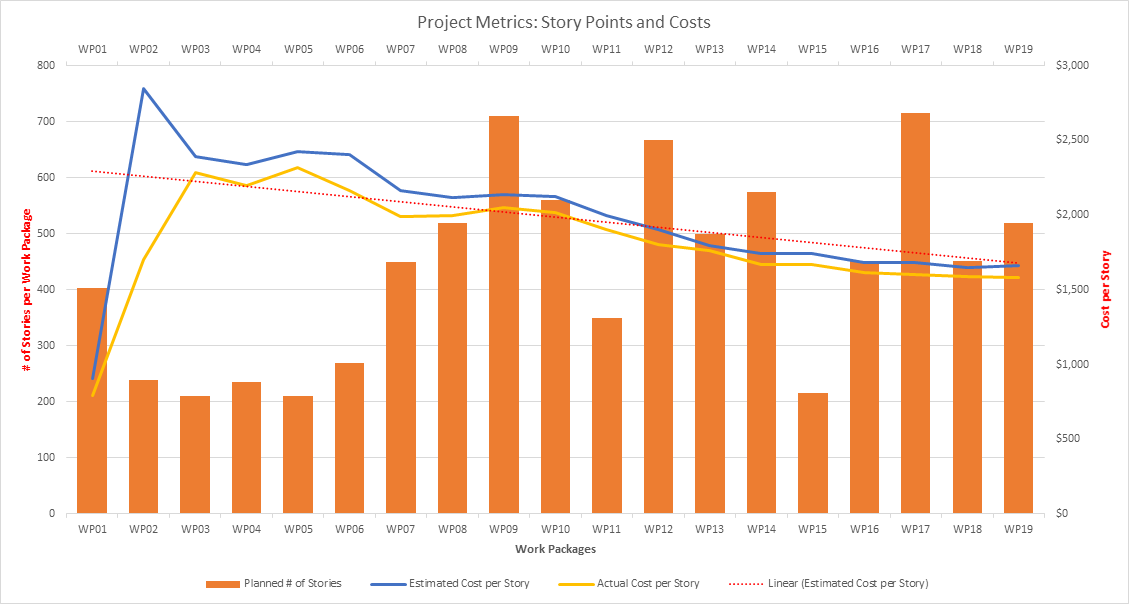

Knowing that a budget overrun was fairly common at the start, Jonah Group leveraged the initial trust they’d built up with the client to identify root causes of the overrun and adjust the team structure for the future. Configuring “work packages” with post-implementation reviews allowed for regular cost oversight analysis. Much like a pilot coordinating with communication towers to make up lost time after a late takeoff, Jonah Group and the pension fund identified team efficiencies that led to a 200 percent reduction in overhead costs later in the project, more than making up for the initial overrun.

“Because it was the first project, we weren’t expecting everything to be perfect,” said Solo. “But we showed them how we would use our processes and team together to fix the problem and move forward.”

Trust between vendor and customer also plays a key role in project success, because it allows both parties to flex when unforeseen situations arise. The real challenges appeared near the end of the project. A project of this scale necessitated the development of separate systems in components, with those components often developed by different teams.

As Technical Architect Abdul Basit described it, the process required “integrating with many services and code built by us, the client, and another vendor. And we had to port over the information from the old system. So as you’re connecting all the dots, things would not always align one to one.”

Whenever the dots didn’t line up, process intervened. The two teams assessed who was better positioned to adjust the codebase, and that team took the reins on the fix. This is where the previously built trust came into play, as Jonah Group would regularly work on code built by the pension fund’s internal team, and vice versa. Even with established processes in place for deciding who would lead and who would support, the trust between the parties kept the project flowing. Allan Wong, the Vice President at Jonah Group, referred to this as “managing to the project objectives instead of just to the contract.”

The difficulty of connecting the dots between multiple teams and technologies was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. After years of entrenched process and culture, teams were suddenly forced to collaborate in a Zoom-only environment. However, the project was able to continue with minimal disturbance; the team again credits the trust foundation they built in the early days.

“We were lucky we built that culture foundation before COVID,” Solo said.

Most importantly for both Jonah Group and the pension fund, the investments they made in early team culture paid off in terms of real dollars at the end. The team’s core productivity measurement (“cost per story point”) was not impacted by the pandemic, owing to the teams’ commitment to each other and the project. Despite the remote work environment, the 5-year long project wrapped up successfully on budget and on time.

Feature image courtesy Wikipedia.