The Accelerator Series is a multi-part spotlight on Canada’s startup accelerators and the people who lead them.

Despite A Limited Sample Size UTEST Insists on Building Great Startups

The students, faculty and recent grads at the University of Toronto sure do have it nice.

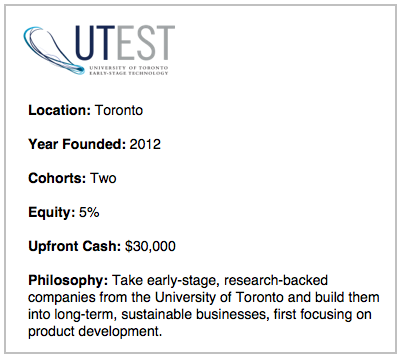

After all, they’re eligible to apply for the University of Toronto Early Stage Technology accelerator, otherwise known as UTEST, possibly one of the most value-packed programs in the entire country at $30,000 investment for just five percent equity.

And with a full-year, long and drawn-out program, it seems like a steal for an early-stage startup. Admittedly though, co-directors Kurtis Scissons and Mike Betts pointed out that the program’s greatest advantage might be its greatest weakness.

“We can’t have these big buck-shot calls for applications for the program that go country wide, but we make up for it in the fact that we do get to work with one of the largest research institutions in the country,” said Betts.

UTEST is much different than the majority of accelerators in Canada for this reason. Much like the University of Waterloo’s VeloCity Garage, one cofounder must be affiliated to the university, and that means UTEST’s sample size of entrepreneurs it gets to choose from is both small and full of potential.

The accelerator is about to receive applicants for its third cohort, in its third year. It accepts five companies per year, however a sixth company was added to its inaugural cohort in 2012, bringing the portfolio total to 11 startups. Scissons and Betts primarily target software plays and “short-term to market companies” (although who doesn’t want that?). Other than that the entrepreneurs need to be both passionate and dedicated.

As for the types of ideas that the entrepreneurs come into the program with, Scissons said the breadth and scope is “huge”. UTEST only requires that they have the IP for the research they’re working on.

This usually points to another interesting fact about the teams: some of the ideas have already been tinkered with for six or seven years before they enter the accelerator and finally incorporate it into a business.

And because the majority of founders are academics with no business experience prior to the program, UTEST often will accept nothing more than an idea. “The companies that we accept in many instances are very early, the stuff is still being built out of a lab and still needs to be made into a product,” said Betts. “For other companies it’s been about putting them in front of the right enterprise customers so that they can sell their solution, because it was largely built by the time they arrived.”

The program’s one-year time span mean companies aren’t rushed into a “three-month sprint where we have to condense everything into a short period of time.” Rather, UTEST spends a lot of time with all five companies, tailoring their mentorship style around each one.

The co-directors call Crowdmark, Whirlscape and Granata as successful examples of how the program can help. Crowdmark might be the best example, given that it’s lead by a now former UofT faculty member who was able to observe a problem within education technology over years. Crowdmark, as the name implies, is an educational assessment platform that crowdsources accredited instructors to mark standardized tests, saving institutions time and money.

It raised a $600,000 round of venture capital in August 2013, the same time that one of UTEST’s original co-directors with Scissons decided to join the startup, in Lyssa Neal. Betts joined on in his current role as a result of this.

All three companies were examples of academics coming to the program with simple ideas, algorithms and visions. “Non of those were companies before they came to UTEST,” said Scissons.

The co-directors sounded proud of their program’s focus on these extremely early-stage companies. For them, being there in the founding stages is as important as watching later-stage success. “There’s a few things that makes UTEST unique, in that were not afraid to take on things that are very much in their infancy,” said Betts.

Arguably another advantage for companies coming into the program is the ownership and funding structure. Every year UTEST collects $75,000 from UofT’s Connaught Fund. It was founded in 1972 when UofT sold its insulin laboratories for $29 million. It’s purpose is to help researchers further their work. The other $75,000 that UTEST gets every year comes from MaRS Innovation.

Because of that funding structure it could be argued that UTEST doesn’t face the same pressure to produce successful companies as other accelerators do, who need to create returns for their limited partner investors. After all, any cash earned from a successful exit from a UTEST startup is reinvested back into the Connaught Fund.

Betts shut that theory down pretty quickly. “It’s under the exact same pressure to try and create homerun companies,” he said. “This isn’t meant to be a charitable endeavour, it’s meant to create successful organizations and sustainable technology companies.”

There’s nearly 20 different options for UofT students who want to turn to entrepreneurship. Whether it be the Rotman School of Business’ Creative Destruction Lab, the Entrepreneurship Hatchery, which is focused on undergraduate engineering students, the Impact Centre for physical sciences students and even more student clubs. But UTEST, as the guys said, is the only “true-blue accelerator” with investment, incubation and entrepreneurship training.

For a minimal equity stake, a fair amount of upfront cash, a year to work on a business and the ability to learn under two guys who sound like they know what they’re doing, UTEST has all the positive’s for those eligible to join. It seems like a no-brainer.

With the accelerator’s third cohort expected to be decided in May, we expect the guys to have some tough decisions ahead of them.

Have you check out the rest of the series?

Part One: Hyperdrive (published January 13)

Part Two: GrowLab (January 20)