Have you ever wondered what the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) or Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) knows about us? How much information have they gathered? How have they gathered it? Do you care? Maybe the biggest question is, why should you care?

The Canadian government is currently attempting to pass Bill C-51. The “Act that may be cited as the Anti-terrorism Act, 2015,” is being fast tracked to (in its own words) “enact the Security of Canada Information Sharing Act and the Secure Air Travel Act, to amend the Criminal Code, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service Act and the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act and to make related and consequential amendments to other Acts.”

As an omnibus bill, C-51 represents a significant and sweeping legislative overhaul. But there are questions about whether it will increase our collective safety amidst a growing wave of concern about the power to surveil and the power to know that will be further bestowed upon these agencies.

Josh Patersons, Executive Director of the BC Civil Liberties Association, spoke at a Vancouver rally against the bill and was unequivocal, saying “Bill C-51 is a threat to our democracy. This bill must be stopped. It will dramatically expand the powers of Canada’s national security agencies and violate the rights of Canadians without making us demonstrably any safer. It’s going to make it easier to detain people without criminal charges and it will criminalize expressions of support for certain political activities. It represents a danger to every single Canadian.”

In the post 9/11 world, reading that “a Senate Judiciary Subcommittee has been holding intensive hearings on invasion of privacy by government agencies” wouldn’t really be news. It wouldn’t be surprising to learn that a Subcommittee said “Federal agents are embarked on a nationwide campaign of wiretapping, snooping and harassment of citizens. The government has been electronically spying on its citizens for years.”

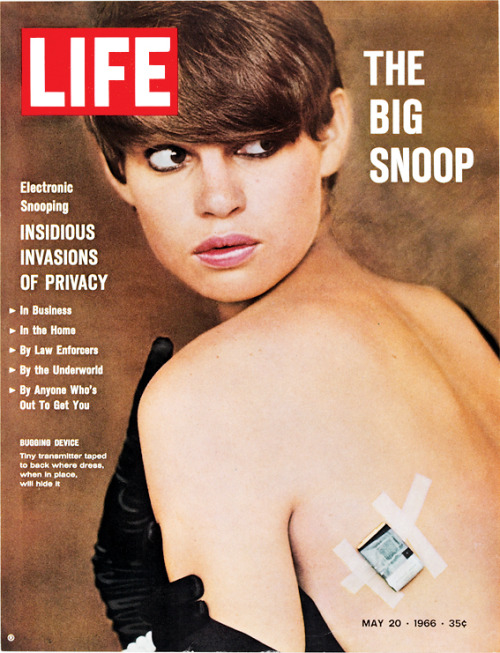

“Communication technology and surveillance have always been strange bedfellows.”

While this sounds like something from a Glenn Greenwald report on Edward Snowden, it’s not. Life magazine’s “The Big Snoop” offered a detailed report on the electronic invasion of privacy. It appeared in the May 20th, 1966 edition. Since the surreptitious unsealing of wax envelopes, communication technology and surveillance have always been strange bedfellows.

Canadians from coast to coast have publicly rallied against the government and Bill C-51. However, some citizens hold to the thought that “Bill C-51 is no big deal, because I don’t have anything to hide.” In response to this type of thinking, Patersons publically offered, “the first thing that I answer to that type of thinking is: we all understand what we do on the toilet, but everyone wants to close the door. There’s no big surprises in there. Privacy is something that is inherent to all of our dignity.”

I posed the same hypothetical question to OpenMedia Executive Director Steve Anderson, and Wes Regan (currently seeking the candidacy for the Green Party in the Vancouver East riding). According to Regan, “expanding powers to spy on, detain, or label dissenting Canadians and First Nations as terrorists or terrorist threats is a big deal even with appropriate oversight, which the current bill also woefully lacks.”

From Anderson’s perspective, “one of the most worrying aspects of this legislation is that all Canadians will have their privacy and democratic rights undermined. You don’t need to have something to hide to be caught up in the government’s surveillance dragnet. If the bill passes, 17 government agencies will have access to your sensitive personal information – and that information could even be passed to foreign governments.”

Regan expanded on the role the Internet is playing as a battleground between the opposing tensions of freedom and security.

“The Internet has been hailed as this great democratic medium, and in many respects it has transformed the world, as access to information and platforms for connecting have given us more data and more ideas to work with than we’ve ever had before,” he said. “However, efforts to regulate the Internet, to install backdoor access to our electronics, to surveil and monitor all of us is not too far removed from the concept of secret police, the kind that were used to crack skulls and disappear people for Stalin or Saddam Hussein.”

Google can’t incarcerate me; the state can. Not all data relationships are created equal.

The tensions become more complicated as the major technological players become involved. I can accept that Google, Facebook, and Apple have a lot of information about me. I accept what these corporations know about me first because they provide a valuable service, but second because they can’t bankrupt me, incarcerate me, or in any other way impede my freedoms; the state can.

Not all data relationships are created equal.

I posed this question to Anderson: for our communication companies and service providers, how fine do you see the line between being complicit with the demands and mechanisms of state surveillance, and actually being able to stay in business without threats of material damage for the government?

He suggested that “telecom service providers have a crucial role to play, and we’d like to see more of them advocate for their users’ privacy rights. Sadly, an expert report recently revealed that telecom companies are still falling short when it comes to standing up for their customers’ privacy, and being transparent about how they do so. All Canadians deserve to know exactly what their ISP is doing to protect them from warrantless privacy intrusions.”

“There are a wide range of practical tools people can use to help safeguard their privacy online,” he added. “https://pack.resetthenet.org/ is a great resource. But at the end of the day, we need a political solution to this problem. No Canadian should need to resort to technical measures to safeguard their privacy from their own government.”

The relationship between a government and its citizenry requires constant recalibration. In the 21st century, technology will act as the intermediary.