The ‘Startup Growth Series’ showcases stories of entrepreneurs that have overcome obstacles in order to expand their businesses in Canada and abroad.

Three weeks into his new role as Executive Director of the DMZ in early 2015, Abdullah Snobar said no to one million dollars.

At the time, Snobar was new, and in some ways, so was the DMZ. Just the year prior, the startup incubator had rebranded from The Ryerson Digital Media Zone with a new name and stated purpose. Originally operating as a co-working community for Toronto startups and Ryerson students, the organization planned to become a startup accelerator focused on helping companies scale.

Speaking to BetaKit, Snobar explained how one key decision early in his tenure helped set the course for the type of organization DMZ would become and how it would choose to support entrepreneurs.

An offer you can’t refuse

“A few weeks into my role, I had a meeting with a high-net-worth individual,” Snobar said.

That individual was a prominent Canadian investor who told Snobar they wanted to donate $1 million to the DMZ.

“In my mind, I’m thinking ‘this is great! Talk about making things happen.”

“I swear to you, I wish I was exaggerating. They actually thought they could come and ask for an equity piece of every company.”

“In the next meeting,” he continued, “the person in question said they wanted to give the donation, but only if the DMZ built a board, made them chair of the board, hired a few of their friends, and paid them small salaries. And they wanted equity from every company that joined [the DMZ]. I swear to you, I wish I was exaggerating. They actually thought they could come and ask for an equity piece of every company.”

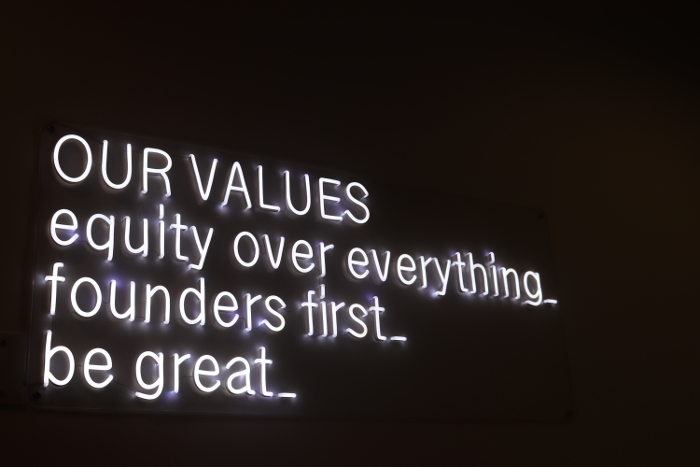

To this donor, asking for the moon seemed a fair bargain. To Snobar, it was in direct violation of the DMZ’s founder-first values. How can an organization that teaches founders to avoid deals with bad terms fund that work through a deal with bad terms?

Snobar also had to face the pragmatic reality of leadership: since the accelerator does not receive any direct government funding—Snobar said the DMZ receives approximately half of its funding from Ryerson, a small percentage via startups paying subsidized rent, with the remainder from corporate partnerships and paying clients—turning down $1 million could significantly hamper its operational capacity.

Snobar turned to Sheldon Levy, then President of Ryerson, and the founder of the DMZ, for guidance. “[Levy] said ‘absolutely not; tell them not even a chance,’” said Snobar.

After that meeting, Snobar knew he had the institutional support that would allow the DMZ to live its values. He also had learned a key lesson that would drive the DMZ’s growth: only work with partners that provide value over the long term.

“No,” “Maybe,” “Yes (but)”

In his time as Executive Director, Snobar has witnessed an evolution in attitudes towards innovation hubs from corporate partners.

“Generally speaking, [it] started off initially as a hard no from corporates,” said Snobar. “They said they’ll do everything on their own.”

This “no” from corporates, said Snobar, was indicative of the mentality that big corporates in Canada either didn’t understand the startup ecosystem or wanted to own the innovation narrative for themselves.

A few years ago, we began to hear more “maybe” responses, continued Snobar, referring to 2016 and 2017. “But the maybe came with a lot of challenges: time and legal constraints. The thing is that [corporates in Canada] are slow to move.”

Over time, as the constraints began to loosen, the demands increased.

“Now I’d say it’s definitely a yes,” Snobar said. “But with that yes, these larger entities come with a number of deal-breaking conditions.”

Those conditions often include demands for exclusivity (which can be limiting for startups), control over programming and startup selection (which limits the expertise of the accelerator), and unreasonable expectations of unicorn-like growth during a cohort period (limited patience).

As the Canadian tech ecosystem has gained prominence, Snobar said that potential corporate partners are often surprised when their demands are met with a response they’re not familiar with hearing: no.

“We want to see more corporates engaging with the startup ecosystem,” he said. “And as we work to bring more stakeholders to the table, it’s important that we leave the oven for the breadmakers. In other words, if we want to reach new levels of startup success in Canada, corporates should recognize that there are incubators and accelerators who have been churning out incredible companies. They don’t just want to be a side lab for corporates to dictate their innovation goals. We need to work together to find their sweet spot in the ecosystem.”

Process over results

When corporate partners aren’t asking to jump right to the finish line, often they’re looking down at their feet. Snobar noted that Canadian corporates focus too much on immediate return on investment, and not enough on long term potential and growth.

“Canadians are known for the attitude we have in terms of being very nice, we want to make sure that everything’s risk averse, clean and easy, that we have consensus around the team over what’s happening,” said Snobar.

“Relative to the States, of course we’re tiny. But it doesn’t matter. We should be able to leverage that better than we’re doing right now.”

According to Snobar, Canadian risk aversion drives the focus on process over results. The Executive Director put the Canadian approach in contrast with American partners the DMZ has engaged with.

“[They’re] honestly a bit relentless,” he said. “They’re hungry. They want to do more, they want to see more, and they’re willing to put things in many baskets to see what will work. And they want to move quickly on it and don’t care how it’s getting done as long as someone is doing it.”

While the DMZ is proud of its Canadian roots, Snobar said the accelerator is building its growth plan from “a global perspective.”

“Now we’re going to start going beyond the borders of Canada,” he said. “Now we give first right of refusal to Canadians but move on beyond that because we have to be level headed and realize we need to be able to do the things we want to do. At that point, you take the money from where you can based on your values not being compromised.”

But that doesn’t mean it’s giving up on Canada. Instead, Snobar said the DMZ wants to be the example that sparks change across the country.

“We want to build that ‘FOMO’ effect, and build out the results and continue showing people what they’re missing out on, that they could be a part of. Show them the reality of things.”

Snobar was blunt, however, with a prediction that things won’t change unless Canadian corporate partners develop a sense of urgency to become good partners and compete at a global scale.

“Some can blame it on size, but I can name six countries, three that are smaller than we are, that are still doing better than we are in terms of actual competitiveness and impact,” Snobar said. “Relative to the States, of course we’re tiny. But it doesn’t matter. We should be able to leverage that better than we’re doing right now.”

Snobar pointed to Canada’s diversity, strong education system and talent pipeline, and government support of the innovation economy as advantages Canada can better leverage.

“We have all the ingredients we need to win,” he said.