In early February, TikTok Canada and a new advocacy group quietly held a presentation for digital creators and online influencers, telling them that the Online Streaming Act, tabled by the federal government just one week earlier, could harm their international success and earnings potential.

The presenters encouraged digital creators to “make [their] voice heard” on the legislation, which would require some tech platforms to make Canadian content discoverable and contribute to cultural funding in the country.

One government source characterized the lobbying efforts as tantamount to a foreign tech company partnering with a Canadian organization to misrepresent the government’s policy positions and goals.

“Disappointed is an understatement,” they said.

Digital First Canada executive director Scott Benzie told attendees in the Feb. 9 presentation that creators risked having their content de-prioritized abroad if TikTok was required to manipulate its algorithm to promote Canadian content to domestic users to comply with the Online Streaming Act. The presentation was hosted by TikTok’s head of Canada public policy, Steve de Eyre, and advertised by the company to its mailing list.

The act, currently being debated in Parliament, is the federal heritage ministry’s second attempt at giving the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) the ability to subject some online tech platforms such as Netflix, Disney Plus, Amazon Prime, YouTube and Spotify to similar Canadian content discoverability rules as broadcast and radio outlets. Tech companies subject to the regulation would also be required to contribute to funding Canadian content.

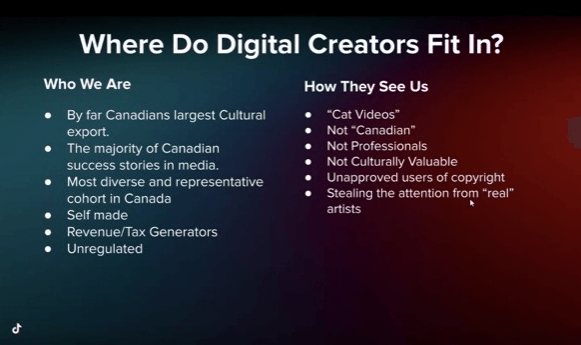

Slides from the presentation, obtained by BetaKit, drew comparisons between digital creators’ commercial success and cultural relevance to a global audience and “how [policymakers] see us.” They claimed policymakers considered creators not professional or culturally valuable, stealing attention from ‘real’ artists and as the creators of “cat videos,” the latter a reference to comments from Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez. The presentation also claims that with digital creators’ work not qualifying as ‘Canadian content’ under existing rules, getting that work certified would be overly cumbersome.

“It was a bit uncomfortable because it was clear they were talking about things that I’m not sure were entirely true,” said a member of the Canadian arts and culture industry who attended the presentation and asked to remain anonymous to protect relationships with TikTok.

The heritage ministry declined multiple requests from BetaKit to comment on the presentation or the organizations involved in this story, but it’s clear the efforts have drawn ire.

“Disappointed is an understatement,” said a government source who requested anonymity as they weren’t authorized to speak publicly on the matter. They characterized the lobbying efforts as tantamount to a foreign tech company partnering with a Canadian organization to misrepresent the government’s policy positions and goals.

C-11: highly debatable

While the TikTok Canada presentation came just days after the introduction of the Online Streaming Act, known in Parliament as C-11, fierce debate on internet content legislation predates the bill’s inception.

Canada’s arts and cultural institutions and member organizations have been largely supportive of C-11, calling it an important step forward for making Canadian music, television, and movies more visible to consumers in the internet age.

“It goes a long way to making it easier for Canadians to find Canadian stories and Canadian music,” said Margaret McGuffin, chief executive officer of Music Publishers Canada, who pointed out that Indigenous, French, and regional artists can have difficulty reaching new audiences.

But some critics are unsatisfied with repeated assertions from Rodriguez that the bill fixed the flaws of its predecessor, C-10. That bill died on the order paper last year after sustained blowback to the removal of a clause protecting user-generated content. That clause, which exempts content such as videos made by digital creators, social media influencers, or everyday Canadians, was re-inserted into C-11. Critics say, however, that the new bill’s overly broad scope could give the CRTC ability to regulate virtually the entire internet, including platforms and apps that traffic in user-generated content.

“The potential overreach in terms of discoverability is very real. … I don’t think there’s any doubt the CRTC will create some kind of threshold, but we don’t know where that is,” said Michael Geist, the Canada Research Chair in Internet and E-Commerce Law at the University of Ottawa and a vocal critic of the bill.

Geist added that there was “a potential for real harm” if the government got into the user-generated content space, and questioned the premise that Canadian artists and creators face challenges being discovered online by Canadian audiences.

CRTC Chair Ian Scott Confirms It Yet Again: Bill C-11 Includes Regulatory Power On User Contenthttps://t.co/pIk06VDYIf pic.twitter.com/3ZyUuEoViB

— Michael Geist (@mgeist) June 1, 2022

Former CRTC vice-chair Peter Menzies has also raised concerns to the Toronto Star that the ministry’s promise of a clear policy directive to the CRTC isn’t a safeguard, noting that such directives can be superseded by future governments or interpreted differently by the regulator.

But a senior government official from the heritage ministry told BetaKit that the government has no interest in regulating social media platforms with business models reliant on user-generated content, such as TikTok or Snap Inc., the company behind Snapchat.

“From the department’s perspective, given the current business models of those services, the intention is not to scope in the content on those services,” the official said.“There is a provision in the bill that specifies that a social media service only dealing in user-uploaded content … is completely excluded.”

The official told BetaKit that the intent of the bill is only to capture internet platforms that act like traditional broadcast and radio.

The official also acknowledged criticisms of the bill’s perceived broadness, but said it was meant to give the government the ability to scope in the professional content on platforms with mixed business models, including YouTube and Spotify.

“I’m confident that by the end of the parliamentary process on Bill C-11, [digital creators] won’t be harmed in any way.”

– Heritage Minister Pablo Rodriguez

YouTube Canada, they said, includes a roughly 50/50 split between professional and user-generated content (professional content includes music videos or entire albums uploaded by musicians and content from traditional broadcasters that is then uploaded to the platform). These platforms with a mixed business model would only face discoverability requirements for the professional content on their platforms, and contribute to Canadian cultural funding commensurate to the percentage of their revenues that come from that content.

The official said the ministry was engaging with the bill’s critics, including social media companies and representatives of digital creators. “If there is a change that needs to be made to the bill, we’re open to that,” they claimed, adding that the CRTC will have to conduct a consultation process as it drafts the regulation.

Minister Rodriguez told BetaKit that the fierce debate and criticisms have opened his eyes to the concerns of digital creators.

“I’m confident that by the end of the parliamentary process on Bill C-11, they won’t be harmed in any way. But, at the same time, this has opened up a conversation about Canada’s digital-first creators,” Rodriguez said.

“Maybe we are late to this conversation, but better late than never, right? Digital-first creators are part of Canadian culture. They contribute to our culture, too. And I think we can do more to support them.”

Grassroots lobbying?

While policy experts and government officials debate the merits of the bill, it may be the creators who get caught in the middle. Multiple members of the arts and culture industry who spoke with BetaKit called the TikTok Canada event misleading to online creators.

“To present the bill in that manner is very disingenuous,” said a music industry professional, who also asked to remain anonymous due to a relationship with TikTok. “I’m sure [disadvantaging digital creators] is not the target of the government.”

Speaking to BetaKit about the February presentation, de Eyre said that TikTok Canada is committed to advocating for the interests of its creators and informing its creator community and policymakers of potential unintended consequences of the legislation.

He added that the company agrees with C-11 as Rodriguez has described it, but argued the current drafting of the legislation could subject a large percentage of content on the app to the act. If the app were subject to discoverability requirements, he said, independent creators would face significant hurdles in receiving Canadian content certification, and could risk being demoted in favour of more established, traditional artists. TikTok Canada isn’t against regulation, he said, pointing to its recent positive feedback on the government’s online harms bill.

“We’re committed to working with the government and all parties and stakeholders to ensure that the bill can achieve its policy objectives when it comes to protecting digital creators,” he said.

“We’re committed to working with the government and all parties and stakeholders to ensure that the bill can achieve its policy objectives when it comes to protecting digital creators.”

– Steve de Eyre, TikTok Canada

TikTok Canada logged 14 meetings since January with members of Parliament and heritage staffers, including Rodriguez’s chief of staff and Bloc Quebecois member of Parliament Martin Champoux, the vice-chair of the standing committee on Canadian Heritage, to discuss issues related to arts and culture and broadcasting, according to the federal lobbyist registry.

The company registered an additional lobbyist one day before the Online Streaming Act was introduced to “engage federal officials on policies to support digital-first content creators and foster the creation, discoverability and exportability of Canadian cultural content online, including Indigenous and French-language content,” according to its company’s lobbyist registration.

The company’s registration said it was also interested in lobbying around addressing illegal content online, and broadly on the topics of privacy, data security and copyright.

The February presentation for digital creators, described by one attendee as a “grassroots lobbying effort,” took a scrappier tone than TikTok Canada’s public statements on C-11. But Benzie, who has been vocal with his critiques on Twitter and elsewhere, said there was nothing clandestine about the presentation, and claimed its assertions weren’t misleading to creators.

“Yes, the outcomes [of the legislation] are not guaranteed, but letting creators know the risk and to speak up if they have concerns is not a controversy,” he said.

Benzie added that Digital First Canada had, as a result of its outreach, brought two TikTok creators and a YouTuber in front of the heritage committee to discuss their concerns with the bill.

“Digital creators don’t have a lobby group or an organized voice, unlike the traditional industry. Why are people so afraid of this?” he asked. “We encouraged them to be active on legislation that could negatively affect them.”

While the presentation contained a disclaimer that Benzie’s views were his own and not those of TikTok Canada, both organizations appear unified in their efforts. In a briefing document for creators sent in advance of the presentation, obtained by BetaKit, TikTok Canada encouraged creators to join Digital First Canada if they wanted to get involved with the bill.

Support from the Canadian arm of a global social media giant is a big vote of confidence for a new organization. Jérôme Payette, the director general of the Association des profesionnels de l’edition musicale, an industry group for Quebec music publishers questioned the origins of Digital First Canada, noting the advocacy group was only recently formed during the debate around Bill C-10.

“It’s not clear who they get their funding from and they don’t have any asks for the platforms — they only seem to be against Bill C-11,” Payette said.

Benzie faced similar questions from MP Steve Bittle, parliamentary secretary to the heritage minister, during his presentation to the heritage committee on a separate bill in late March.

“These platforms have incredible unchecked power over these creators. These are some of the largest companies in the world, and in looking at your website and your Twitter account, both for you personally and for your organization, they are absent anything except for C-10,” said Bittle.

During testimony a witness (Scott Benzie) claiming to represent a "grassroots" organization that advocates for digital artists admits he's actually funded by Google & TikTok.

He lied to a Parliamentary committee about his funding when he appeared in March. pic.twitter.com/AaYmqJ8I7K

— Chris Bittle (@Chris_Bittle) May 31, 2022

Benzie is also the chief executive officer of Buffer Festival, an annual film festival of digital creators that began at the Canadian Film Centre. Benzie said he and a colleague at Buffer Festival launched Digital First Canada after C-10 was dropped to advocate for the interests of online creators, who have no formal organization working on their behalf. He said the organization plans to operate within Buffer Foundation, a registered not-for-profit.

As a new organization, Digital First Canada is still finalizing its board. Benzie said he expects it to feature industry representation from TikTok, YouTube, and Henrys Canada, with the majority (80 percent) composed of content creators, and Super Simple Songs co-founder Morghan Fortier (who recently presented to the heritage committee on C-11) serving as the board chair. Benzie said the organization is 80 percent self-funded from its Buffer Festival activities, but has received some funding from TikTok, YouTube, and Henrys Canada.

“But [it’s] not a lot of money,” Benzie said, adding that the financial support was not a secret. Benzie also noted that no one has been paid through the Buffer Foundation, including himself.

“Yes, the outcomes [of the legislation] are not guaranteed, but letting creators know the risk and to speak up if they have concerns is not a controversy.”

– Scott Benzie

According to Buffer Foundation’s annual filings with Corporations Canada, the not-for-profit is a non-soliciting corporation, meaning it receives less than $10,000 per year in gifts and donations. Benzie said in the seven years he’s been with Buffer, the organization only received a “very small” award sponsorship in 2017, worth less than $10,000. While YouTube has collaborated with the festival to bring in speakers and host a dinner, he said nothing was paid to Buffer.

“I appreciate the criticism that this organization wouldn’t exist without the backing of platforms — that’s probably true, but it doesn’t make it OK,” he told BetaKit. Benzie said the Canadian Arts Council, Canadian Media Fund, and Bell Fund all turned Buffer Festival down for funding. “They didn’t recognize digital creation as part of their mandate. So we turned to people who do.”

Benzie also disputed the characterization of Digital First Canada as being anti-C-11. He said he’s supportive of legislation’s efforts to regulate major platforms like Netflix and Disney Plus and thinks “this bill can be fixed.”

He also denied that the group has no position on other issues affecting creators. “Our mandate isn’t set by the platform — I have a lot of problems with the platform,” he said. “I think TikTok should tomorrow introduce a system where they pay their creators. Every conversation we have with digital creators who focus on TikTok, those are the first things we hear out of their mouths and we 100 percent support them.”

Facing criticisms it has not adequately financially supported creators compared to other platforms, TikTok announced on May 9 that it was launching a program to allow advertisers to purchase ad spots next to the top four percent of videos in the app’s For You feed, and for users with 100,000 followers or more to be eligible for the first stage of an advertising revenue-sharing program. The program will begin in the U.S., with other markets to follow.

“Canary in the coal mine”

For all the questions and concerns raised to BetaKit regarding Digital First Canada and TikTok Canada’s unified advocacy against Bill C-11 to creators behind the scenes, it must be noted that other content platforms like YouTube Canada have gone public with their C-11 issues. The company has said the legislation could eat into Canadian creators’ foreign revenue if the government forces it to promote Canadian content.

In a briefing provided to the Canadian Press, YouTube asserted C-11 could lead Canadian users to click away from promoted Canadian content, and downgrade that content in international markets.

“I think personally it’s that tech doesn’t want to be regulated locally, and on any issue.”

YouTube Canada’s head of government affairs, Jeanette Patell, also said the text of the bill gives the CRTC the scope to oversee amateur home videos. Speaking during a panel at the National Cultural Summit in Ottawa in early May, Patell said the company understands that full-length music videos by professionals should be subject to the regulation, but called for an explicit exclusion of home or amateur videos.

If the government wants an “option in the future” to regulate users’ videos, “that’s a conversation we need to have,” Patell said, per the Canadian Press.

One day before Rodriguez was set to appear before the heritage committee to discuss C-11, Patell appeared on the Brandon Gonez Show on YouTube to explain her concerns about the bill, and YouTube Canada shared an “update” from Patell on C-11 on the Google Blog.

“We aren’t opposed to regulation, and we will continue to do our part to support the Canadian creator economy. And we agree that an official music video should be regulated the same way whether it’s shown on YouTube or TV,” Patell wrote. “But we believe it’s possible to support Canadian musicians, artists and storytellers without putting the livelihoods of thousands of digital Canadian creators at risk.”

Patell’s blog also said the company supported Digital First Canada, and encouraged creators to “add [their] voice to the conversation” by signing its petition.

According to the federal lobbyist registry, lobbyists for Google Canada, YouTube Canada’s parent company, have met with parliamentarians and heritage staffers, including Rodriguez, about media and broadcasting issues 16 times since January.

Payette drew a line from tech lobbying around C-11 to the fierce debate in 2019 around the European Union’s decision to introduce new copyright rules that granted publishers greater control over their content by preventing content-sharing platforms from displaying unlicensed copyrighted content. Tech giants Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, and Microsoft spent millions lobbying against the legislation, claiming it could harm innovation in Europe or harm internet freedom.

“There were a lot of fears of things that would supposedly happen…and I think some people truly believed that,” he said.

Payette said the fears stoked by tech companies is “something we need to worry about [here],” adding that C-11 is just one of three bills currently before Parliament focusing on regulations for tech and internet giants.

“[Critics] tend to focus on only one article [of C-11], spreading fear and saying that things could possibly happen because of one article — it’s just completely exaggerated and does not show a complete understanding or nuance of how the broadcasting system has been working in Canada.”

The industry member who attended TikTok Canada and Digital First Canada’s presentation drew similar conclusions. They speculated that TikTok’s participation, along with the broader tech pushback, is rooted in a desire to avoid regulation.

“I think personally it’s that tech doesn’t want to be regulated locally, and on any issue. … They always come back and [claim] free speech, or say those who are trying to regulate are trying to break the internet, which is pretty simplified,” they said.

“Entertainment is always the canary in the coal mine for most issues.”

Feature image courtesy Solen Feyissa via Flickr (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Correction: an earlier version of this article said the current construction of Digital First Canada’s board of directors features industry representation from TikTok, YouTube, and Henrys Canada, based upon information received from Scott Benzie. We’ve updated it to reflect that Benzie expects these companies to be part of his board when it is finalized.