Memoto’s lifelogging camera was one of the more intriguing, and potentially invasive, Kickstarter projects I saw in 2012. But I didn’t hesitate to back it, not because I thought it would be a great product — which it turned out to be — but because the wider implications of lifelogging in general are something I’m eager to explore.

Closer to shipping, the Swedish company behind the project changed its name to Narrative, and the product to the Narrative Clip. The name change was not surprising — Memoto was a confusing and often difficult one to parse — since the word “narrative” conveys so much of what we do online every day. We share snippets of our lives, which coalesce into short- and long-term stories.

Now that Narrative is available, shipping to Kickstarter backers and soon those who pre-ordered it for $279, can we conclude that the story was worth reading? Will Memoto’s legacy influence our behaviour, and the products of other companies, or is the Narrative Clip just another example of an isolated wearable product doomed to be remembered for its good intentions?

At this point, the Narrative Clip fits right in the middle, a good idea held back by buggy software and first-generation hardware. But it also points to a future where cameras that monitor, log and, potentially capture sensitive material, are not just perched on walls but on bags, lapels and belts.

What is lifelogging?

Lifelogging refers to the idea of comprehensively logging the minutiae of our lives. In many ways, we already do this, quite actively, too: we tweet, check in, review, photograph and provide context not only to ourselves, but our friends, families and followers. At the moment, most of this activity is done actively and consciously, a process of determination. But services like Foursquare and Google Now are creating a passive environment for this type of activity, too: constant background polling determine, in broad strokes, where we are and what we’re doing. Algorithms and past behaviour combine with that data to infer our companions and our moods.

Narrative Clip fits into that paradigm by furthering the idea of passive capture. The device is a small plastic square measuring 36x36x9mm, weighing a paltry 20 grams. It houses no buttons: on one side is a series of four LEDs used to indicate battery charge and, when the device’s face is double-tapped, a manual photo; the other side contains a microUSB input with a rubber covering. The back has a strong, metal clip and in one corner of the front is the small 5MP camera sensor and lens. It’s extremely unobtrusive, almost filtering itself out of existence; in the winter, it blends well with a jacket or pair of jeans, and could easily be mistaken for a step counter like a Fitbit.

How it works

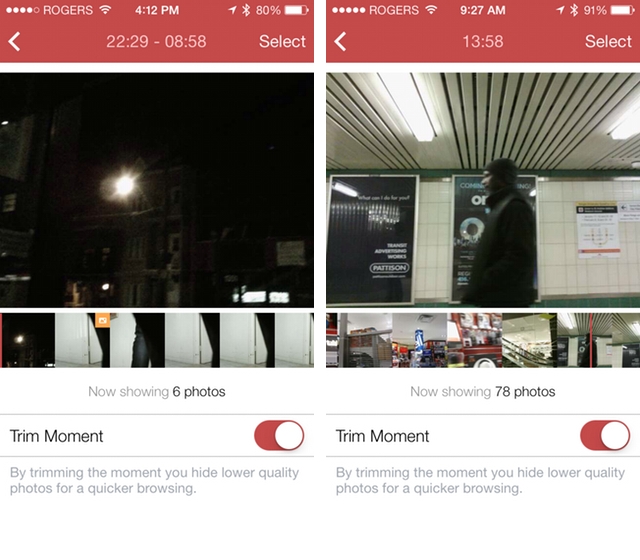

Narrative Clip works by taking a photo every 30 seconds. This is its primary function, and the basis of its lifelogging mantra. While, as stated, it is possible to manually line up and capture a photo by double-tapping the front of the accessory, it will continue capturing a photo every half minute until its tiny battery is exhausted or its 8GB of internal memory is full.

Throughout Memoto’s post-Kickstarter gestation period, the Swedish company kept its backers apprised of problems sourcing the right parts and ensuring the device was resistant to the harsh climates of the northern hemisphere. Also present inside the clip are an accelerometer, magnetometer and GPS module. The 5MP camera sensor is made by Omnivision and is backside illuminated, with a 70-degree field of vision. Photo quality can be good, but as you’ll see below, movement and grain combine to make capturing great photos very challenging.

Because the Narrative Clip lacks WiFi connectivity, it must be plugged in to a computer to fulfil its ultimate purpose: a photographic diary of the minutiae of one’s life. The Windows or OS X-based app is merely a middleman — it uses the USB drive to upload your photos to Narrative’s cloud server. This could potentially be done directly using an Android or iOS device, but no such functionality currently exists. Ultimately, though, this is a modern wearable product that relies as much on its cloud sync/smartphone combination as it does on its hardware capabilities.

The first year of cloud sync and storage is free, and Narrative plans to roll out long-term subscription plans with its product in late 2014. Think the Dropcam business model, where you buy the excellent hardware and gain minimal functionality from its free plan, while permanent recording and storage comes with a monthly fee. If the Narrative Clip proves to be an indispensable part of my life, I’ll have no problem paying $10/month to keep the company afloat — storage is extremely expensive, after all — but we’ll have to see.

So is it any good?

So is it any good?

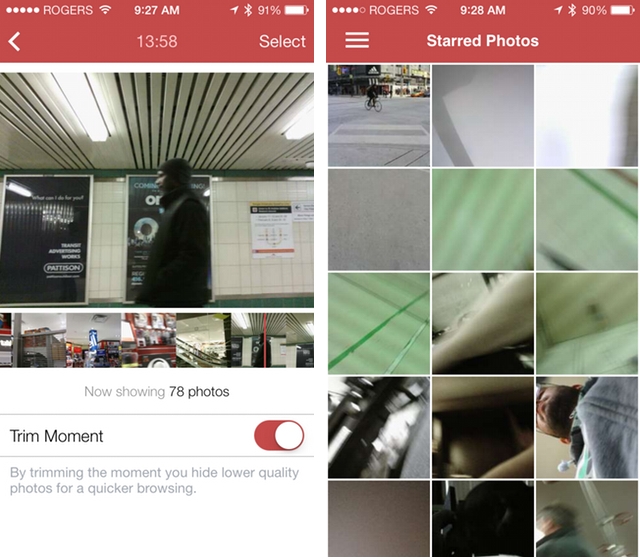

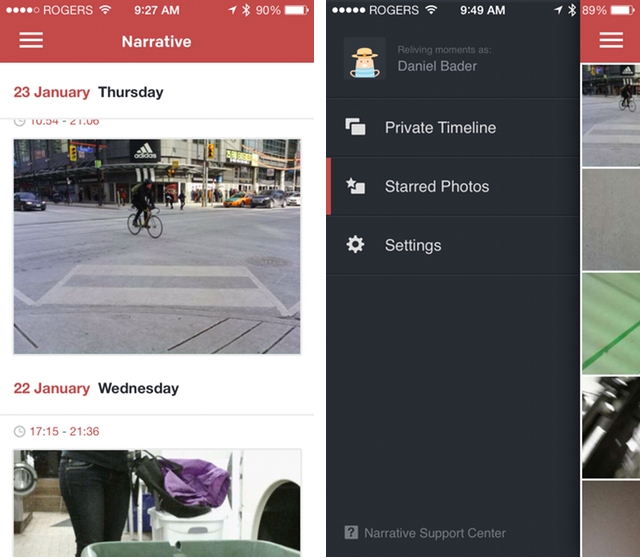

That depends on what your expectations are for the Narrative Clip, and for lifelogging itself. It’s unlikely that you’re going to capture many life-altering or award-winning photos, though the camera and software combination does a good job of automatically weeding out the cream from the crop. After uploading to Narrative’s cloud server, the iOS or Android app divides your photos into Moments, which comprise of a specific time period determined by the app. These Moments cannot be changed — your photos will be grouped together forever, in that order — but there are some meaningful attempts, using GPS and the accelerometer, to group together similar photos and obfuscate the bad ones.

The best photos I took were while walking down a street or standing, unmoving, in a subway car. Unlike tapping the side of a Google Glass, or pointing a Galaxy Gear watch at an unsuspecting subject, no one took notice of this small clip attached to my jacket pocket or belt. It blended in nicely with the messy accessories of winter: gloves, hats, scarves, and perhaps activity trackers. No one looked strangely at the rounded square affixed to my lapel while at dinner, either, though a few friends asked me why the hell I insisted on become more like a cyborg every day (this without having ever worn Google Glass, so heads up).

Narrative’s inconspicuousness is both its best and worst feature: it blends in with almost every situation, and invites little notice; but it is also extremely easy to misplace, which I did several times before finding it either a) on the ground a few feet behind me, or b) stuffed in a pocket after entering a restroom, not wanting to risk taking a photo of myself in action.

Lifelogging submits that you will log all aspects of life, both mundane and exciting. But I found, after a few days, that not only is my life extremely monotonous — I wouldn’t trust the clip to stay affixed while on a rollercoaster, for instance, and I have never gone skydiving — but there were many situations that I found it inappropriate to continue wearing the Narrative Clip, and would then forget to re-attach it. Moreover, I would often attach the camera to my jacket, and forget to transfer it to my person when removing it; as a result, many of my photos were of white walls.

This doesn’t discount the idea of the Narrative Clip, and I think it will be far more interesting during the summer, when I can attach it to a t-shirt without worrying about it being covered by a jacket or scarf. More importantly, by the summer Narrative will have likely resolved many of software kinks early adopters like myself have been facing… and there are quite a few.

Ghosts in the Machine

I really understand Narrative founder and CEO, Martin Källström, when he explained in an interview last July that “there is an immense amount of emotion with photos.” To him, Narrative is not about creepily taking photos of the world, but about helping you remember exactly what you were doing. Even a slight brushstroke — the side of someone’s face, or the hue of a wallpaper — can evince memories that may have been forgotten. Narrative’s Clip isn’t so much about recalling what you did yesterday, but a year ago. It’s Timehop for your boring life, which is likely more exciting than it appears. Even after a week, when memories begin fading, opening the Narrative app on my phone helps recall not only the events, but the emotions, I was feeling at the time.

Thousands of Kickstarter backers and pre-orderers evidently agree: Narrative, despite its deficiencies, is a hit. The battery, however, isn’t: I found it to last less than the two days of usage promised in the spec sheet. And the OS X-based uploading program, the lynchpin of the whole operation, was extremely unreliable, failing to upload photos on more than one occasion.

The iOS and Android apps, on the other hand, immediately impress. Hundreds of photos can be quickly scrolled through to gain a sense of time and place, and individual ones can be starred as “favourites” for later perusal, downloaded for local viewing, or made a cover photo for that particular moment. Because the Narrative Clip allows shots to be taken manually by double-tapping on the front at any time, those purposeful shots are immediately made favourites, regardless of their quality.

Potential

The Narrative Clip is, at the moment, barely more than a second set of eyes with an SD card. Being a first-gen product, it does not take advantage of the immense amount of data it captures daily — hundreds of photos and thousands of megabytes. But this will change. Källström has a vision for the company, and plans to improve not only the hardware’s underlying firmware, but the algorithms used to parse all that visual data, in the months and years to come.

Right now, the Narrative Clip is a story without an ending. It’s one in a series of wearable devices that hinges on the idea that there are few boundaries to privacy in the public sphere and we should all just assume that we are being captured and logged, both by the government and one another, at all times. With just one of two people in a city of millions using a Narrative Clip, the implications are minor, but I foresee a time, just a few years from now, where such devices are the norm, and include audio. Then we’re dealing with serious privacy issues.

On its own, Narrative Clip née Memoto is a lovingly-crafted experiment, but like fellow Kickstarter darling, Pebble, it could morph over time into a viable and audacious commercial product.