Thanks to their penchant for selfies and social media and the perception that they feel entitled to jobs after years of incurring student debt, millennials are often dubbed the selfish generation. But for a generation that earned that moniker, it’s interesting that research shows that millennials are more interested in finding work with purpose beyond profit that benefits society.

Toronto-based Paddle is trying to tackle both the problems of young people struggling to find jobs and their desire to find meaning in their work. Early this year, Paddle raised $700,000 from angel investors and the RBC Generator Fund in Toronto. US-based Hunt Holdings also participated in the round. The company, which now has a team of eight, used the funding to hire more engineering, design, and product team members.

The career advice platform works in two parts: it provides an assessment to help users understand who they are and what motivates them, and provides a recommendation section including actionable content — such as videos, articles, and online courses — meant to help users more effectively find success in sectors different the one they may have studied.

Though a major part of Paddle’s philosophy is about finding meaning and motivation, it’s also about remaining realistic about the fast-changing job market — many of the jobs that exist today will be replaced by technology, so workers need to be better prepared to jump between jobs.

“People so far have been guided and trained to think in one track. And that’s not the natural human condition.”

“Young people are switching jobs much faster than people in the past. Our parents’ generation might have had two or three jobs in their career, but in our generation we already know we’re switching jobs at least 12 times in our lifetime, and most of these jobs will disappear,” said Matthew Thomas, co-founder of Paddle. “It’s more important to be adaptable than to be an expert at something.”

Paddle is based on the premise that education today is too specialized; from a young age, students are told by parents and schools to find one thing they’re good at early on, choose a program in university, and become an expert. While he was at McKinsey as a business analyst in 2012, Thomas interviewed 150 people identified as “amazing job jumpers” to find out how they did this successfully. “Job jumpers have a bad reputation in society. People say they aren’t focused and don’t know what they want. We wanted to turn that narrative completely on its head,” said Thomas.

“Our top tool in our toolkit is listening to people in their career who are interested in making the jump, and building tools to help them succeed. Motivation is something that should be core to these decisions.”

One of the examples from the study included former Coca-Cola VP of Environment and Water Resources Jeff Seabright, whose background included public sector stints at the US Senate and President Clinton’s White House Task Force on Climate Change, but little private sector experience. He was appointed to the role after Coca-Cola was banned from soft drink production in South India because of its excessive water consumption. Because of his background, Seabright could give a strong business case for water conservation by convincing the company to conduct a water risk analysis process for its 20 business units — apparently, it was the first time that Coca-Cola had seen such a thorough analysis on how many resources the company consumed.

Thomas’ research found that these people have the ability to apply their talents seamlessly across business, nonprofit, and government jobs, as these areas often have intersections that aren’t always obvious. “A lot of skills are more transferable than people realize,” said Thomas.

Thomas then took that research — published in the Harvard Business Review — to the Presidio Institute in 2013, and turned it into an executive training program the following year where top organizations like The White House and BlackRock were paying millions of dollars.

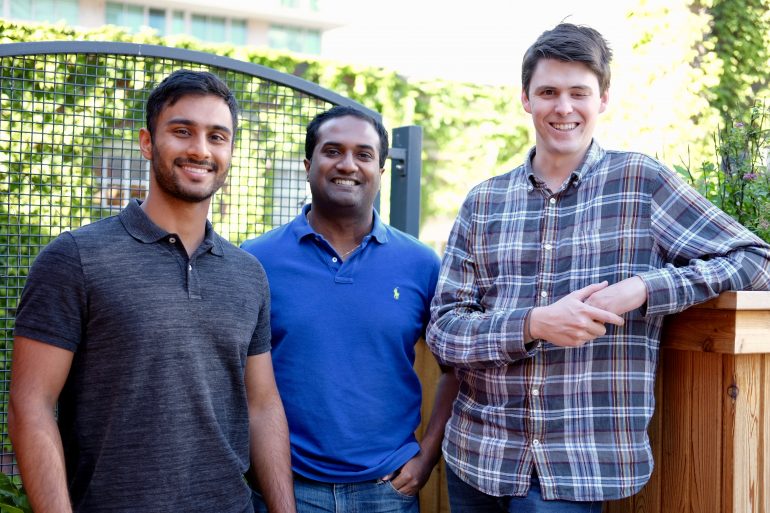

“And then I met my team, and I thought, how can we go from training 24 people a year to training 24 million people a year?” said Thomas, calling Paddle’s founding team integral to making the platform approachable for the masses. Sid Bhargava, who leads engineering, helped to build the foundation, while head of product Pat Whelan’s background helped with creating a platform that reflected Matt’s research.

“Our top tool in our toolkit is listening to people in their career who are interested in making the jump, and building tools to help them succeed. Motivation is something that should be core to these decisions and it’s often the reason why you leave a job,” said Whelan. “And our recommendations platform is ongoing, so it’s a tailored experience that helps you every week to build habits.”

To date, Stanford Business School has purchased the platform for their grad business schools, as well as the University of Toronto and Ivey Business School. Currently, Paddle is working on integrating with TakingITGlobal and TalentEgg. The company also wants to expand to India, a culture that places a high emphasis on education.

“You’re more transferable than you think, and Paddle brings out the idea that you can fit in multiple sectors and have an impact in multiple ways,” said Thomas. “People so far have been guided and trained to think in one track. And that’s not the natural human condition, we’re born to do multiple things.”